Introduction

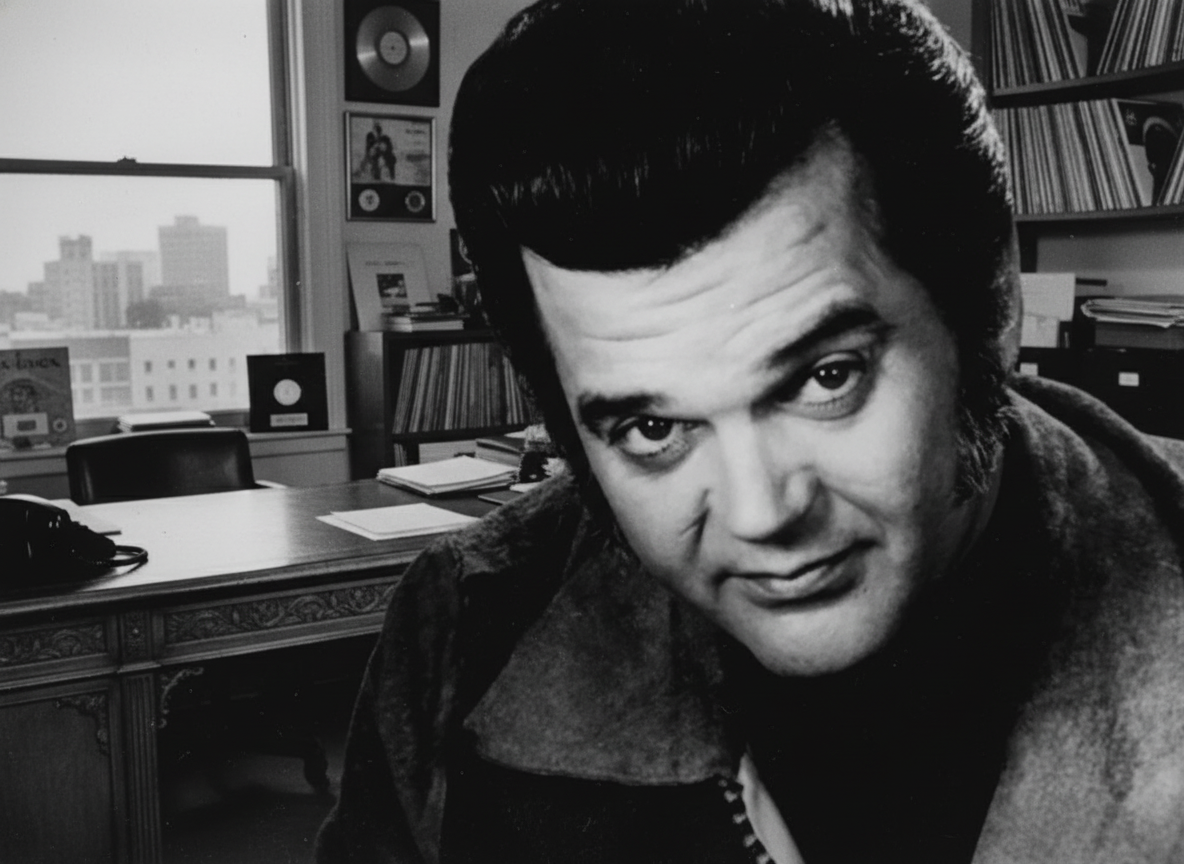

In the annals of American music, the term “copyright” often conjures images of bitter plagiarism disputes—think George Harrison’s unconscious “borrowing” or the modern-day “Blurred Lines” fallout. Yet, for Conway Twitty, the legal theater was rarely about the theft of a melody. Instead, his career and the three decades following his death in 1993 provide a masterclass in a different kind of judicial struggle: the preservation of sovereignty over a legacy.

Contrary to urban legends that often follow prolific hitmakers, Twitty was never embroiled in a major plagiarism lawsuit regarding his fifty-five number-one singles. His reputation for “intellectual honesty” in his songwriting remained remarkably intact. However, the absence of creative theft did not equate to a lack of litigation. Twitty was a meticulous businessman who understood that in the music industry, the paradigm of power lies not just in the writing of the song, but in the control of its digital and physical destination.

The most defining legal chapter of his life—and one of the most famous in American tax law—was Jenkins v. Commissioner (1983). While not a plagiarism case, it was a battle over the “commercial image” of a star. When his restaurant chain, “Twitty Burger,” collapsed, Twitty personally repaid his investors to protect his professional standing. He then attempted to deduct these payments as business expenses. The IRS resisted, but Twitty won a landmark victory. The court ruled that an artist’s reputation is a tangible business asset—a precedent so unique that the judge famously closed the ruling with a poem, “Ode to Conway Twitty.”

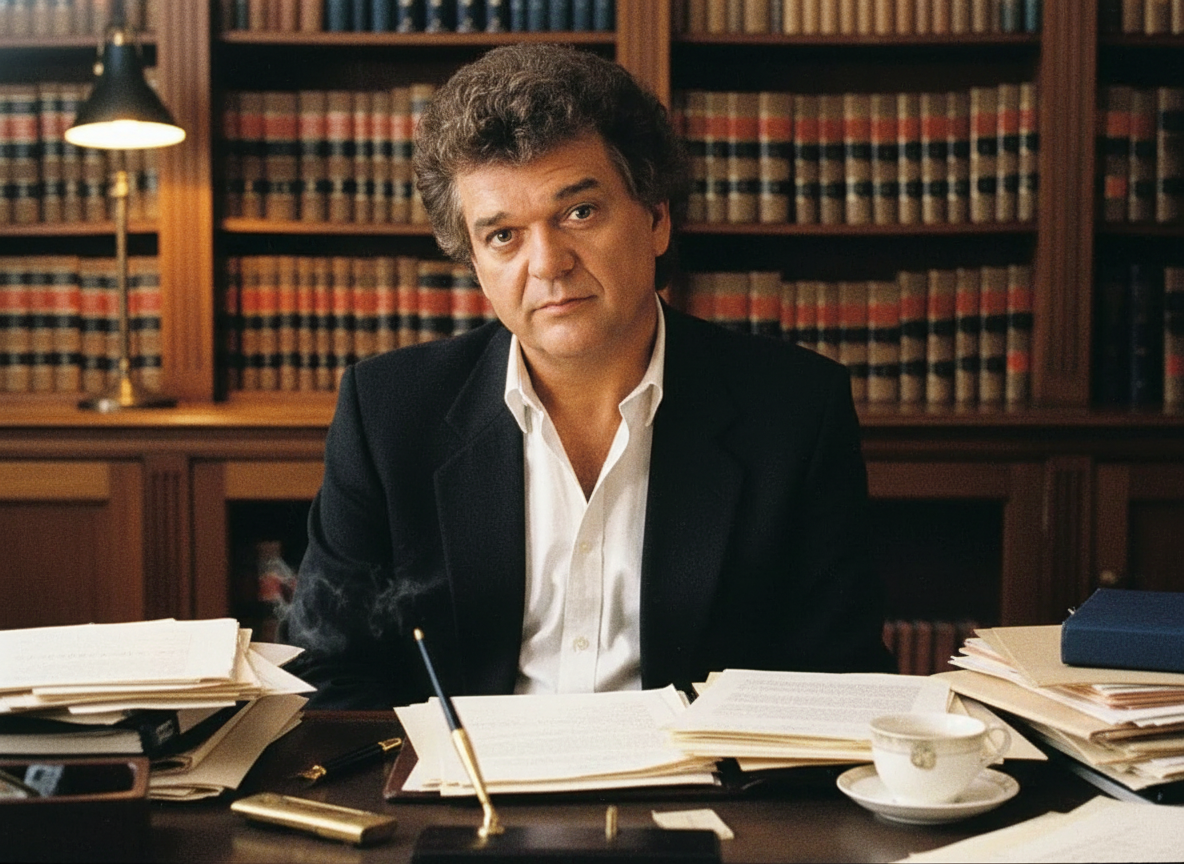

The true “copyright” wars, however, ignited after his death. In 2008, a decade and a half after he passed, his children filed a high-profile suit against Sony/ATV Music Publishing. The crux of the matter was not “who wrote the song,” but “who owns the right to it.” The children alleged they had been misled when signing away publishing and recording interests in 1990. This case, alongside the perpetual friction with his widow, Dee Henry Jenkins, over royalty “double-dipping,” underscores a painful nuance of the industry: a legacy can be structurally sound yet legally fragile.

As we look back from the vantage point of 2025, it is clear that Twitty’s legal legacy is one of integrity rather than infringement. He did not steal the music of others; he spent his life—and his family spent theirs—fighting to ensure that the music he built was not stolen from him by the machinery of probate or the fine print of corporate contracts. The resolution of these disputes serves as a cautionary tale: for a legend, the final curtain call is often followed by a thirty-year encore in the courtroom.