Introduction

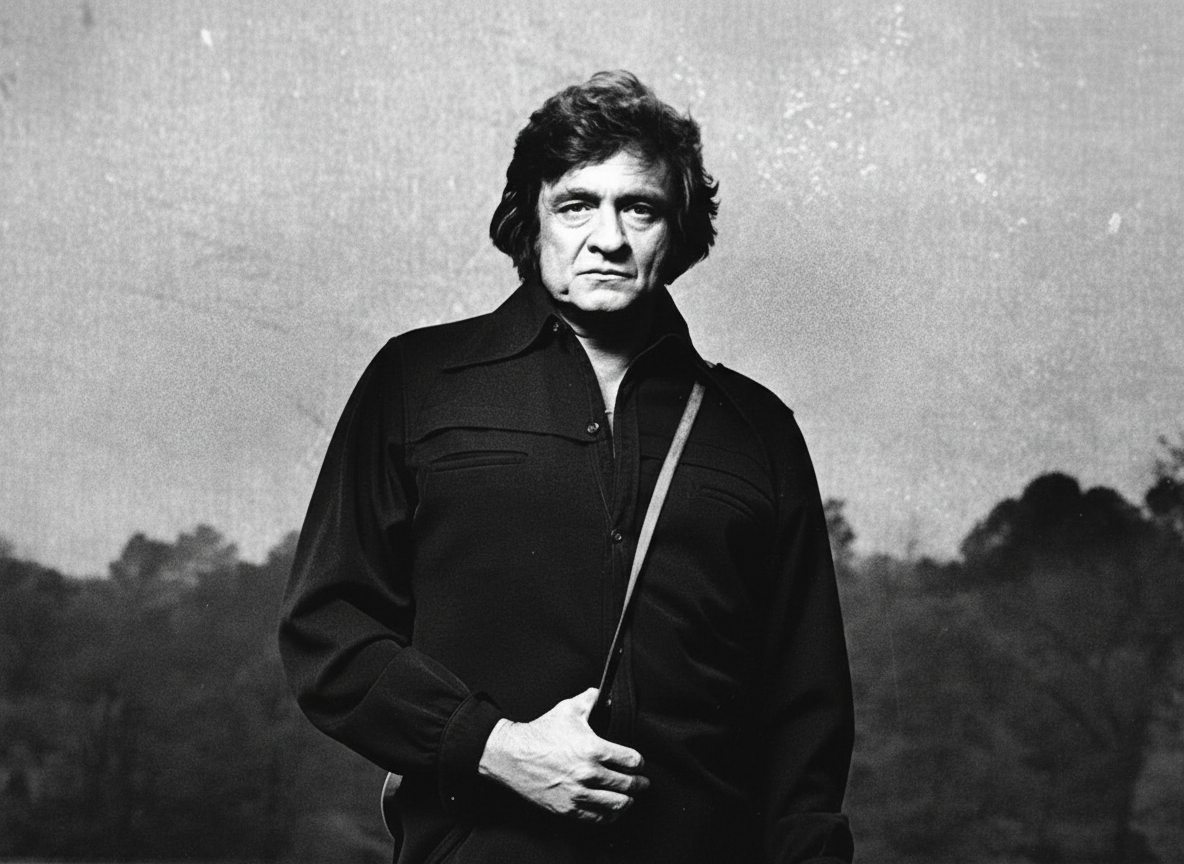

The voice of Johnny Cash was never merely an instrument of entertainment; it was a moral landscape. It was a gravelly, baritone architecture that stood for a specific, unvarnished American truth. In November 2025, that architectural integrity became the center of a landmark legal collision in a Nashville federal court. The John R. Cash Revocable Trust—the entity charged with safeguarding the legacy of the “Man in Black”—filed a high-stakes lawsuit against The Coca-Cola Company, alleging that the beverage giant “pirated” Cash’s identity through a calculated act of vocal mimicry in a nationwide advertising campaign.

The “Golden Thread” of this conflict lies in the tension between corporate marketing and the sanctity of the human persona. According to the complaint, Coca-Cola’s “Fan Work Is Thirsty Work” campaign featured a commercial titled “Go the Distance,” which utilized a tribute artist, Shawn Barker, to simulate Cash’s distinctive vocal texture and aesthetic presence without the estate’s authorization. This was not a casual homage; the estate contends it was a deliberate attempt to siphon the “intrinsic value” of a legend to enrich a commercial brand. The irony is palpable: a corporation that has spent a century branding itself as “The Real Thing” is now accused of profiting from a fabricated one.

This case serves as the first major test for Tennessee’s Ensuring Likeness Voice and Image Security (ELVIS) Act, a revolutionary piece of legislation enacted in 2024. While the act was widely heralded as a shield against the rising tide of generative AI and deepfakes, this lawsuit proves its utility extends to more traditional forms of impersonation. The statute explicitly protects a performer’s voice from nonconsensual commercial exploitation, defining “voice” not just as an original recording, but as a simulation that is “readily identifiable and attributable” to the individual. By invoking this law, the Cash estate is not merely seeking a payout; they are asserting a new paradigm of human rights in the digital age—the right to the exclusive ownership of one’s own auditory DNA.

The contextual depth of the struggle is articulated most sharply by the estate’s lead counsel, Tim Warnock. His assertion that “stealing the voice of an artist is theft of his integrity, identity, and humanity” elevates the dispute from a contractual disagreement to an ontological defense. John Carter Cash, the artist’s son, echoed this sentiment, noting that while the family frequently licenses Johnny’s music for legitimate uses (such as “Ragged Old Flag” for past Super Bowl broadcasts), the act of “counterfeiting” the man himself is a line that cannot be crossed.

As the litigation moves forward, it raises a chilling question for the 2025 cultural landscape: In a world where the “simulacrum” is increasingly indistinguishable from the “original,” can the law truly preserve the uniqueness of the human spirit? The resolution of Cash v. Coca-Cola will likely determine the fate of legacy management for the next century. It is a reminder that while a man can be buried, his voice remains a sovereign territory—one that, even decades after his death, still demands a fierce, black-clad defense.