INTRODUCTION

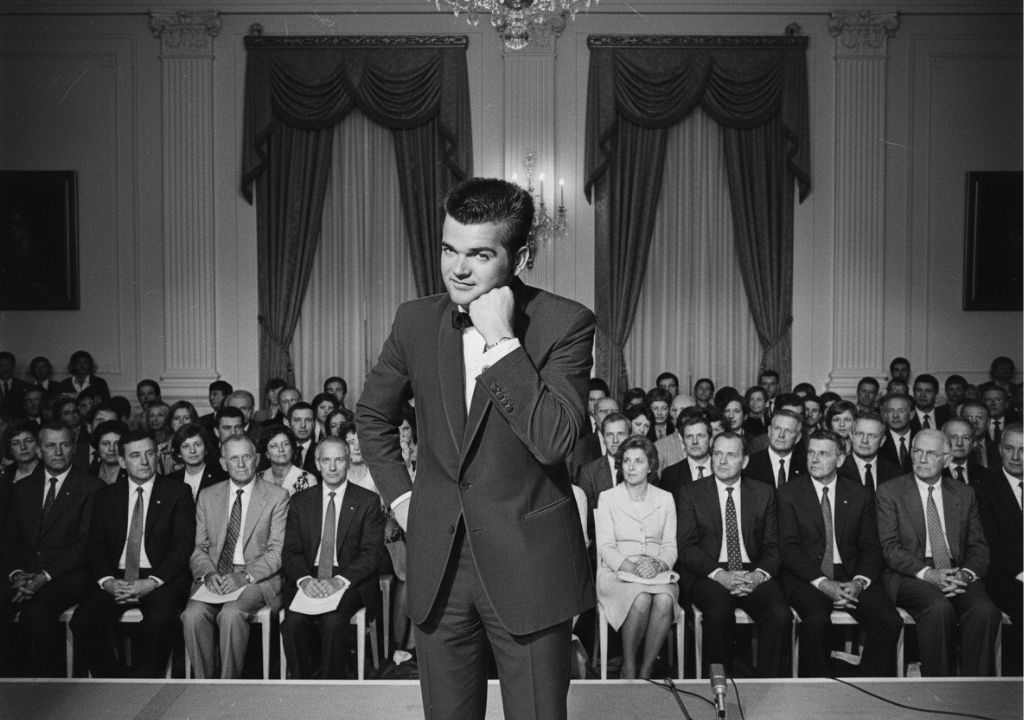

The East Room of the White House is usually a sanctuary for the rigid protocols of state dinners and classical recitals, but on April 17, 1978, the air vibrated with a distinctly southern frequency. Standing beneath the crystal chandeliers, Conway Twitty—the “High Priest of Country Music”—prepared to execute a high-stakes performance for President Jimmy Carter. This was not merely a musical engagement; it was a sophisticated cultural validation. For a president who campaigned on the image of the “New South,” inviting Twitty to the capital was a meticulous move to align the administration with the visceral, working-class narratives that defined the American heartland. As the first notes of the guitar cut through the formal silence, the boundary between the Mississippi Delta and the halls of global power began to dissolve.

THE DETAILED STORY

The narrative of Conway Twitty’s performance for the 39th President remains a masterclass in the intersection of celebrity and civic duty. Jimmy Carter, arguably the most musically literate occupant of the Oval Office in the 20th century, sought to utilize the “Program for Country Music Celebration” to showcase the genre as the soul of American democracy. Twitty, appearing both as a solo titan and in his record-breaking partnership with Loretta Lynn, brought a level of professional precision that silenced any lingering skepticism from the Washington elite. He performed “It’s Only Make Believe” and “Hello Darlin'” with the same meticulous, whispered intensity that had turned his live shows into something akin to a religious revival.

What made this performance particularly significant was Twitty’s adherence to his “philosophy of silence.” Even in the presence of the Commander-in-Chief, Twitty refused to engage in the typical stage banter or political pandering that often accompanies such appearances. He allowed the structural integrity of the songs—ballads of longing, regret, and resilience—to speak for themselves. This stoic approach mirrored the gravity of the office he was visiting, creating a paradigm where the artist and the President occupied a shared space of quiet authority. The setlist, which featured the iconic duet “Louisiana Woman, Mississippi Man,” served as a sonic map of the very regions Carter aimed to revitalize, proving that the American ballad was a potent tool of national identity.

Beyond the East Room, Twitty’s “presidential” legacy was further cemented by a unique diplomatic contribution: the Russian-language version of “Hello Darlin’.” Recorded for the Apollo-Soyuz mission as a gesture of international goodwill, the track was broadcast from space, effectively making Twitty a global emissary of American culture. By the time he concluded his White House set with “God Bless America Again,” it was clear that his impact transcended the Billboard charts. He had successfully demonstrated that the “High Priest” was not just a title for the stage, but a role that carried the weight of a nation’s collective conscience. His performance for Carter remains an authoritative reminder that the most direct path to the American heart often begins with a single, well-placed baritone note.