INTRODUCTION

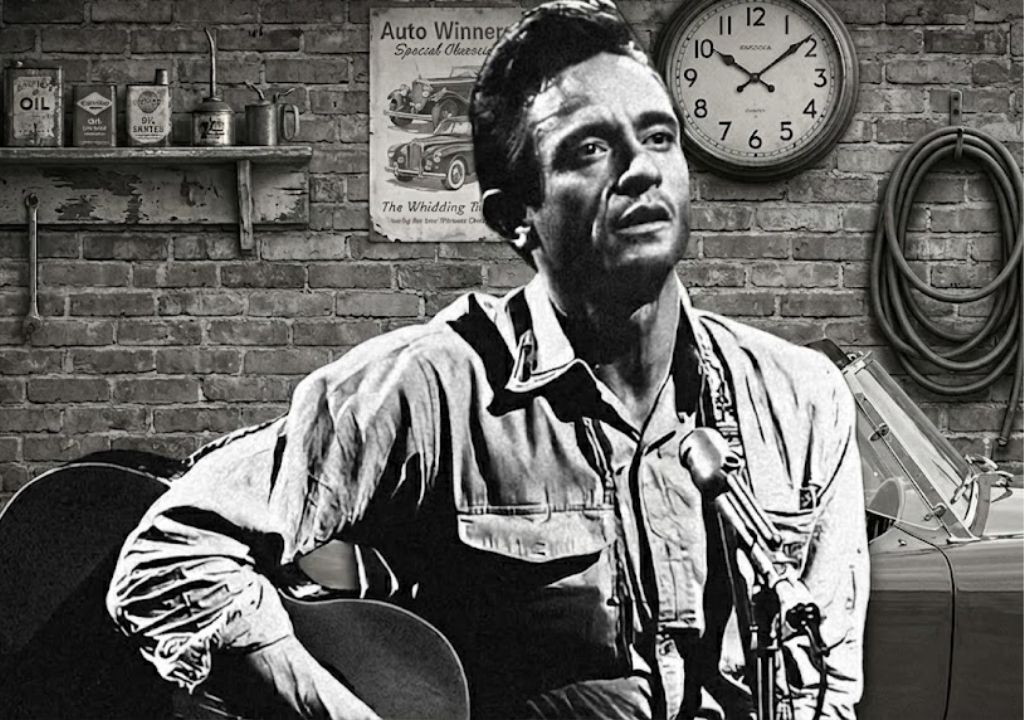

On the morning of January 13, 1968, the heavy iron gates of Folsom State Prison clanged shut behind Johnny Cash, sealing him within a fortress of granite and grievances. The air inside was thick with the scent of floor wax and the palpable electricity of several thousand men who had been systematically stripped of their names and relegated to numbers. As Cash approached the microphone, he did not project the detached aura of a visiting celebrity or the moralizing stance of a preacher. Instead, he stood with a slumped, weary posture that mirrored the existential exhaustion of the inmates themselves. When he began to sing, it wasn’t just a performance; it was a profound act of recognition that bridged the chasm between the free world and the forgotten.

THE DETAILED STORY

The phenomenon of hardened criminals weeping during a Johnny Cash set was not a product of sentimentality, but rather a reaction to a rare encounter with total intellectual and emotional honesty. Cash possessed a unique psychological architecture; though he had never served a long-term sentence himself, his well-documented battles with substance abuse and the internal ghosts of his past gave him a visceral understanding of “the fall.” He did not look at the men in Folsom or San Quentin as monsters, but as tragic figures caught in a cycle of transgression and consequence. This lack of condescension created a sanctuary where the inmates felt safe enough to lower their psychological armor.

Central to this connection was Cash’s refusal to sanitize the human experience. When he sang the infamous line from “Folsom Prison Blues”—about shooting a man in Reno just to watch him die—the resulting roar from the crowd was not a celebration of homicide. Rather, it was a collective exhale of men who finally felt “seen” in their darkest impulses and the subsequent weight of their regret. Cash acted as a mirror, reflecting their humanity back to them without the distortion of societal judgment. His voice, a gravelly baritone that seemed to carry the dust of a thousand lonely roads, served as a conduit for a shared American suffering.

This empathetic paradigm extended beyond the lyrics. Cash meticulously advocated for prison reform, taking his observations from these hallowed halls directly to the halls of Congress. He understood that the “criminal” label often obscured a more complex narrative of poverty, trauma, and the inevitable failure of the human spirit under pressure. By treating the incarcerated with the sovereignty of fellow men, he bypassed their defenses. The tears shed by those in the front rows were an acknowledgment of a man who spoke their language—a language of scars, missed opportunities, and the faint, flickering hope for a redemption that the world had deemed impossible.

Cash’s legacy in these institutions remains a testament to the power of presence. He proved that music, when delivered with a meticulous lack of pretense, functions as a form of social justice. He did not offer them an escape from their cells, but rather a temporary escape from the psychological prison of their own shame. In that shared space, between the rhythm of the guitar and the silence of the yard, Johnny Cash reminded the world that no one is beyond the reach of a dignified, empathetic ear.