INTRODUCTION

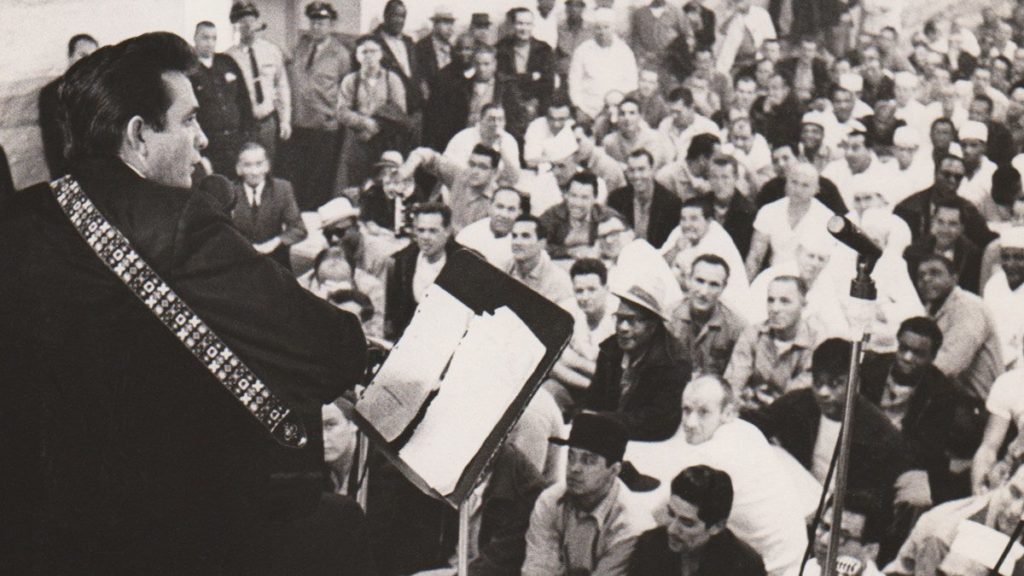

The metallic clatter of heavy weaponry being checked and loaded echoed through the limestone corridors of Folsom State Prison on January 13, 1968. It was a morning defined by a sharp, biting chill—roughly 45 degrees Fahrenheit—but the atmosphere inside the cafeteria was sweltering with a different kind of heat. For the correctional officers stationed on the elevated catwalks, the arrival of Johnny Cash was not a cause for celebration, but a logistical nightmare of the highest order. They did not see a country music star; they saw a potential detonator. With the prison population already simmering under systemic pressures, the administration feared that Cash’s raw, empathetic frequency would be the spark that finally ignited a catastrophic uprising against the institutional status quo.

THE DETAILED STORY

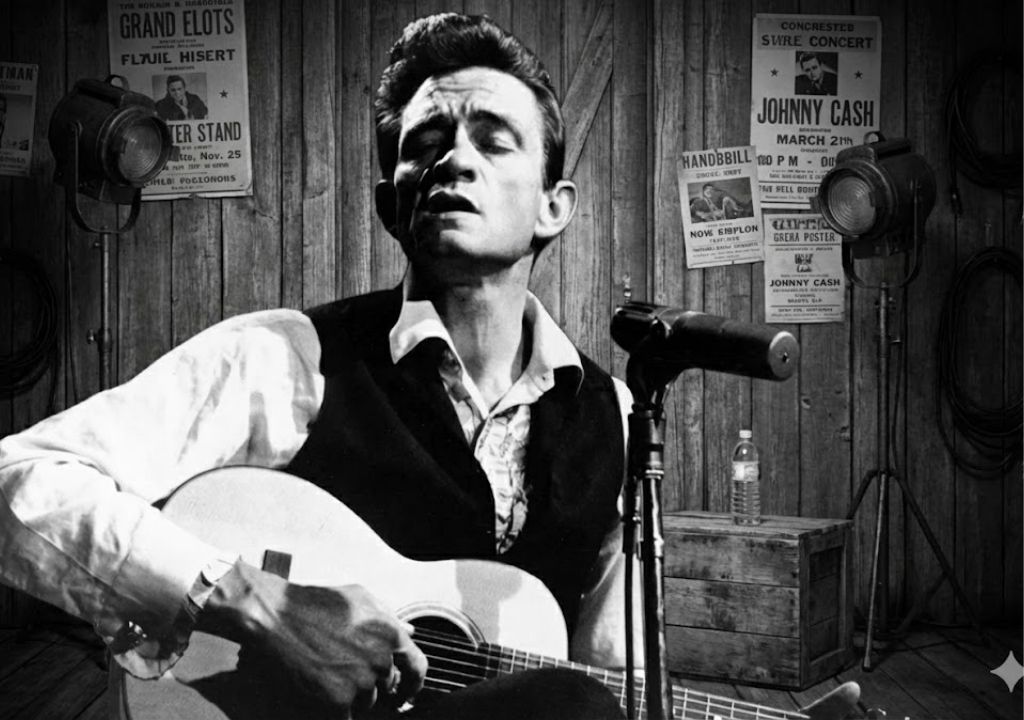

The tension between the stage and the guard towers was a study in psychological warfare. The prison authorities had issued a strict mandate: there was to be no standing, no excessive cheering, and no movement that could be interpreted as a breach of order. For the guards, the paradigm of the prison depended on the absolute dehumanization of the inmates; any recognition of their individual sovereignty was viewed as a threat to security. When Cash stepped onto the plywood riser, he was meticulously aware of the rifles pointed toward the crowd. He navigated this volatile space with a nuanced understanding of power dynamics, knowing that one wrong word could transform the performance into a riot, yet refusing to sanitize his message to appease the wardens.

During the recording of “Folsom Prison Blues,” the guards’ anxiety reached a crescendo. The inmates’ reaction to the line “I shot a man in Reno just to watch him die” was not a spontaneous outburst, but a carefully edited roar added in post-production. In reality, the prisoners remained unnervingly silent, fearing retribution from the armed guards watching their every move. However, Cash’s decision to speak directly to the inmates—complaining about the quality of the water provided by the prison and mocking the restrictive rules—was seen by the administration as a direct subversion of their authority. He was intentionally undermining the hierarchy, positioning himself as an ally to the incarcerated rather than a guest of the state.

This calculated defiance created an inevitable friction. The warden and his staff were convinced that Cash was stoking the embers of resentment, yet they were powerless to stop a man who had the eyes of the nation upon him. Paradoxically, while the guards feared a riot, Cash’s performance served as a sophisticated pressure valve. By articulating the inmates’ pain and frustrations, he provided a cathartic release that likely prevented the very violence the authorities anticipated. He proved that music could achieve a level of social equilibrium that force alone could never maintain.

Cash left Folsom having successfully navigated the most dangerous stage in America. He didn’t just perform a concert; he executed a masterclass in narrative tension, proving that true authority is not found in a rifle, but in the ability to command a room through the sheer force of human connection. The “Man in Black” walked out of the gates, leaving the guards with their order intact, but with their psychological control forever diminished by the echoes of a song.