INTRODUCTION

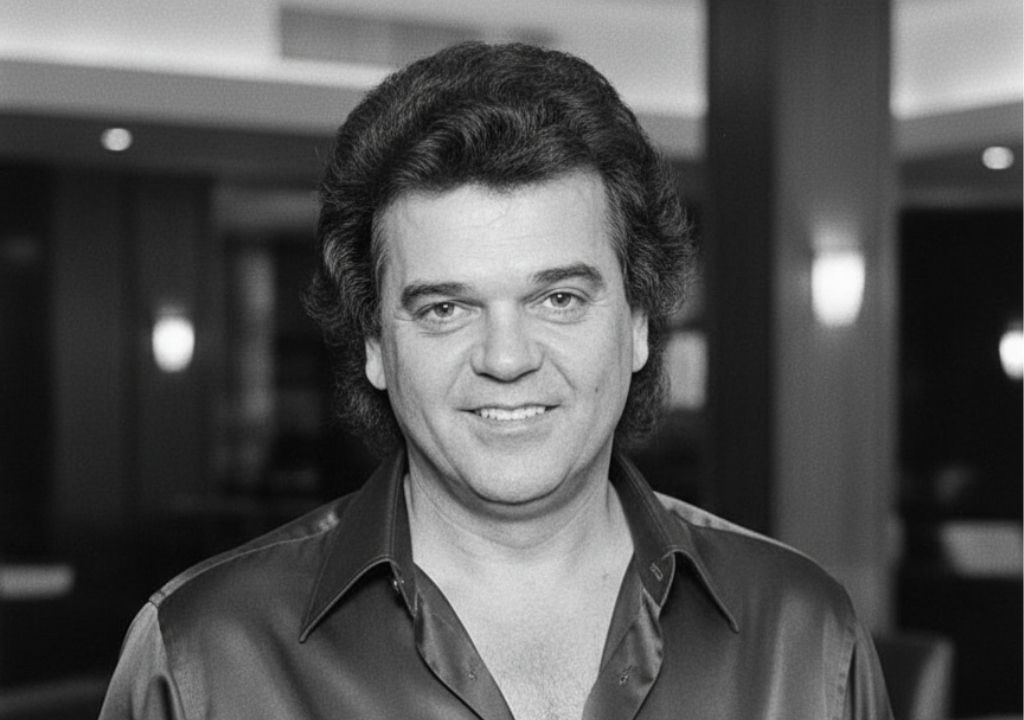

The year was 1964, and the airwaves across the United States were no longer a hospitable environment for the rockabilly architects of the fifties. Harold Lloyd Jenkins, known to a global audience as Conway Twitty, stood in the wings of a crowded auditorium, watching the tectonic plates of the music industry shift with violent precision. The arrival of The Beatles did not merely introduce a new sound; it initiated a total cultural replacement. For Twitty, who had dominated the late fifties with hits like “It’s Only Make Believe,” the sight of the British quartet was a moment of profound, analytical clarity. He recognized that the era of the pompadoured American solo act was being swept away by a wave of European groups, leaving him as a relic of a paradigm that had lost its resonance with the youth of the new decade.

THE DETAILED STORY

The narrative of Conway Twitty’s transition is often framed as a sudden epiphany, but the reality was far more meticulous and industrial. While his contemporaries viewed the British Invasion as a temporary trend to be weathered, Twitty saw it as a definitive signal to exit a burning building. By 1965, he was increasingly disgruntled with the expectations of his rock audience. He famously remarked that he felt his days of providing “background music for sweaty teens” were fundamentally over. The Beatles had redefined the rock-and-roll demographic, moving it toward a psychedelic and experimental energy that Twitty—a man of traditional melodic structures and disciplined vocal delivery—found foreign. Instead of competing with the “Fab Four,” he chose to return to the genre that had always served as his private sanctuary: country music.

This pivot was not without significant risk. In the summer of 1965, Twitty walked off the stage during a performance in New Jersey, essentially firing his rock-and-roll persona in real-time. He spent the next three years fighting for airplay in a Nashville establishment that viewed his rock past with deep-seated skepticism. The nuance of this move was purely strategic; Twitty realized that while the Beatles had taken over the pop charts, the heartland of America remained a fertile ground for the storytelling and emotional resonance of country. He understood that while he could no longer lead a rock revolution, he could meticulously engineer a country dynasty. This gamble paid off in 1968 with “Next in Line,” the first of a record-breaking 55 number-one hits.

Ultimately, Twitty’s reaction to the Beatles was one of professional respect and tactical withdrawal. He didn’t harbor resentment; he recognized a superior competitive force and moved his assets to a different theater of operations. In the grand narrative architecture of his career, the British Invasion was the catalyst that allowed the “High Priest of Country Music” to be born. It raises an authoritative point about the nature of longevity: true icons do not fight the tide of history; they learn to navigate it. By the time the Beatles disbanded in 1970, Conway Twitty had already secured his place as an immovable pillar of the Nashville sound, proving that a retreat in one genre can lead to an immortal conquest in another.