INTRODUCTION

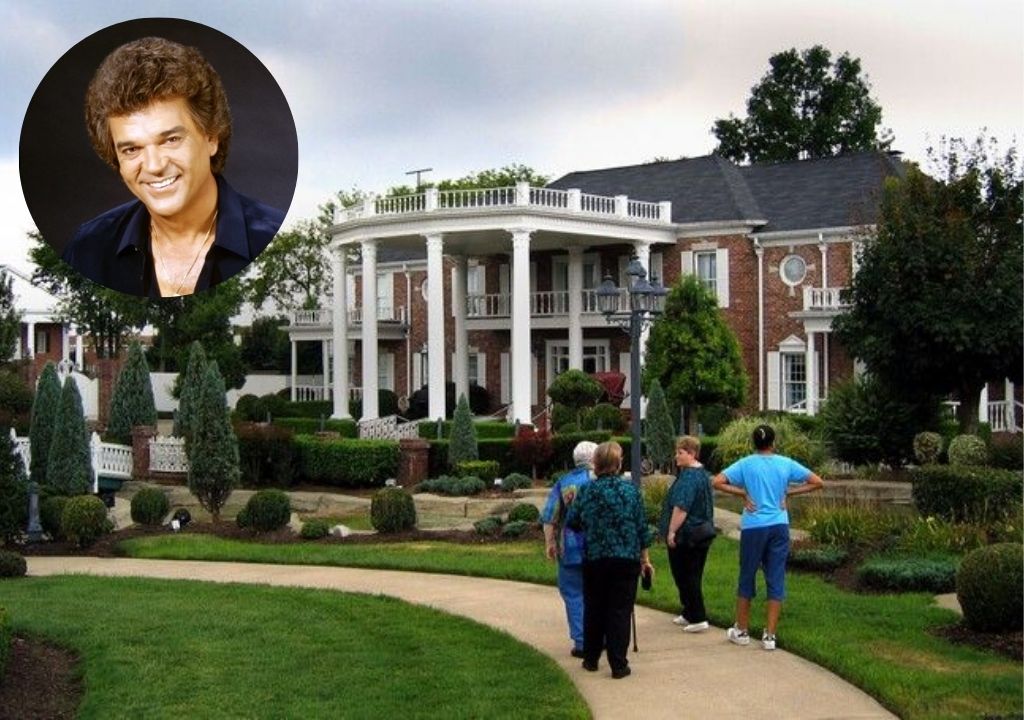

When Harold Lloyd Jenkins broke ground on the $3.5 million complex known as Twitty City in 1982, he intended to construct a fortress of familial unity and fan accessibility. The 33-acre estate, located in the affluent Nashville suburb of Hendersonville, Tennessee, quickly became a pilgrimage site for country music loyalists. Yet, the architectural grandeur of the 24-room mansion stood atop soil that had been a silent witness to the volatile formation of the American frontier. Long before the “Hello Darlin'” sign greeted visitors, this specific corridor of Sumner County served as a strategic and often contested ground, situated mere miles from historic sites like Rock Castle—the oldest standing home in Middle Tennessee—and the remnants of forts designed to repel Native American incursions during the late 18th century.

THE DETAILED STORY

The rumors of paranormal activity within the confines of Twitty City emerged not from a desire for sensationalism, but as a byproduct of the site’s intense historical density. Staff and visitors over the decades have reported meticulous anomalies that suggest the land retains a certain “memory” of its previous occupants. These accounts frequently center on the “Timeless Treasures” shop, where witnesses have documented the sound of clinking porcelain and the subtle movement of toys in wicker chairs. Rather than the morbid tropes of traditional haunting, these occurrences are described by local historians and paranormal researchers as “residual echoes”—vibrations of a domestic life that predates the Jenkins era.

The paradigm of the haunted estate is further complicated by the land’s role during the Civil War. Hendersonville and nearby Gallatin were pivotal hubs of movement for both Union and Confederate forces, with properties like the Monthaven mansion serving as makeshift field hospitals. This proximity has fueled a persistent narrative that the spirits encountered at Twitty City—including reports of a woman’s voice whispering to performers on stage—are displaced figures from a century of conflict. For Conway, the estate was a vision of the future; for the land itself, it was simply another layer in a meticulous geological and social record.

When the Trinity Broadcasting Network assumed control of the property in 1994, the transition from a country music mecca to a global religious broadcasting hub did little to stifle the local lore. Even today, as the property faces redevelopment following the catastrophic tornado of December 2023, the question of the land’s “true” identity remains. The legacy of Twitty City is therefore a nuanced study in human ambition versus the inevitable persistence of history. It suggests that while we may build monuments to our own success, we are merely temporary residents on land that belongs to an older, more silent registry of names. The haunting of Twitty City is not a matter of fear, but an authoritative reminder that every “Hello Darlin'” is an invitation to a conversation with the past.