INTRODUCTION

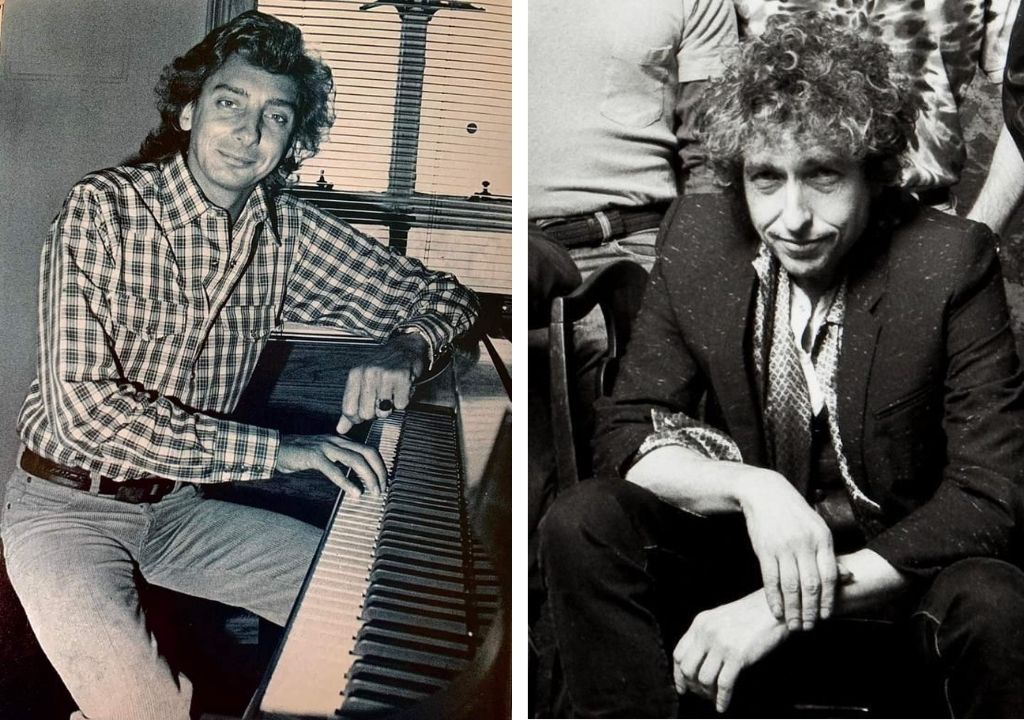

The air inside the recording studio was thick with the scent of high-gloss production and the hum of a $100,000 console. In 1978, a decade defined by the grit of punk and the search for “raw” truth, Barry Manilow stood as a singular, polarizing figure: a Juilliard-trained architect of sound who treated the three-minute pop song as a rigorous mathematical proof. The stakes were not merely commercial, though his record sales were staggering; the real conflict lay in the definition of artistic merit. When Bob Dylan—the high priest of the counterculture—reportedly approached Manilow at a party to tell him, “Don’t stop what you’re doing, man, we’re all inspired by you,” it shattered the binary between “meaningful” folk and “superficial” pop. This endorsement forced a re-evaluation of the Manilow paradigm: was his ability to trigger universal emotion a form of manipulation, or a mastery of the human condition?

THE DETAILED STORY

To call Barry Manilow the “Bob Dylan of Pop” is to engage in a deliberate provocation, yet the comparison yields a meticulous truth regarding their respective influences on American culture. While Dylan dismantled the traditional structure of the song to reveal a fragmented, poetic reality, Manilow sought to perfect that structure to the point of inevitability. His compositions are not merely songs; they are symphonic movements compressed for the radio. In tracks like “Could It Be Magic,” Manilow utilized the harmonic foundations of Chopin’s Prelude in C Minor, Op. 28, No. 20, weaving classical rigor into a Top 40 format. This was not a populist accident; it was a calculated attempt to elevate the medium of the ballad to a level of technical sophistication that his peers rarely attempted.

The controversy surrounding his songwriting ability often stems from a fundamental misunderstanding of “authenticity.” In the 1970s, the music press prioritized the aesthetic of the unpolished, viewing Manilow’s lush arrangements and key-change crescendos as “schmaltz.” However, this critique ignores the nuance of his craftsmanship. Manilow understood that in a fractured world, there is a profound necessity for the resolution of a melody. He occupied the space of the “Great American Songbook” at a time when that tradition was being discarded. Like Dylan, he created a signature sonic language that was immediately identifiable, a feat that requires a level of visionary focus often reserved for the avant-garde.

Ultimately, the friction between the Manilow and Dylan legacies reveals more about the listener than the artist. We are conditioned to believe that depth requires darkness, yet Manilow’s career suggests that the architecture of joy and sentiment is equally complex. His influence is felt in the meticulous production of modern pop titans who understand that a perfect chorus is a feat of engineering. As we move further from the genre wars of the 20th century, the distinction between the “prophet” and the “perfectionist” fades, leaving us with the realization that both men were essentially doing the same thing: translating the invisible vibrations of human experience into a permanent, undeniable record.