INTRODUCTION

The velvet curtains of the Essoldo Theatre in Birkenhead did not merely separate the stage from the stalls; on the night of October 1, 1958, they represented a psychological threshold that Ronald Wycherley was never intended to cross. Carrying a handful of self-penned compositions and a borrowed guitar, the eighteen-year-old Liverpool deckhand sought only to sell his music to the impresario Larry Parnes. Instead, in a move that would become a cornerstone of British rock-and-roll mythology, Parnes pushed the trembling adolescent into the spotlight of a live performance. This baptism by fire transformed the reserved Wycherley into Billy Fury, a name specifically chosen to counteract a shyness so profound it verged on the pathological. This foundational irony—a man named for rage who possessed the temperament of a poet—would define the most successful solo career of the pre-Beatles era.

THE DETAILED STORY

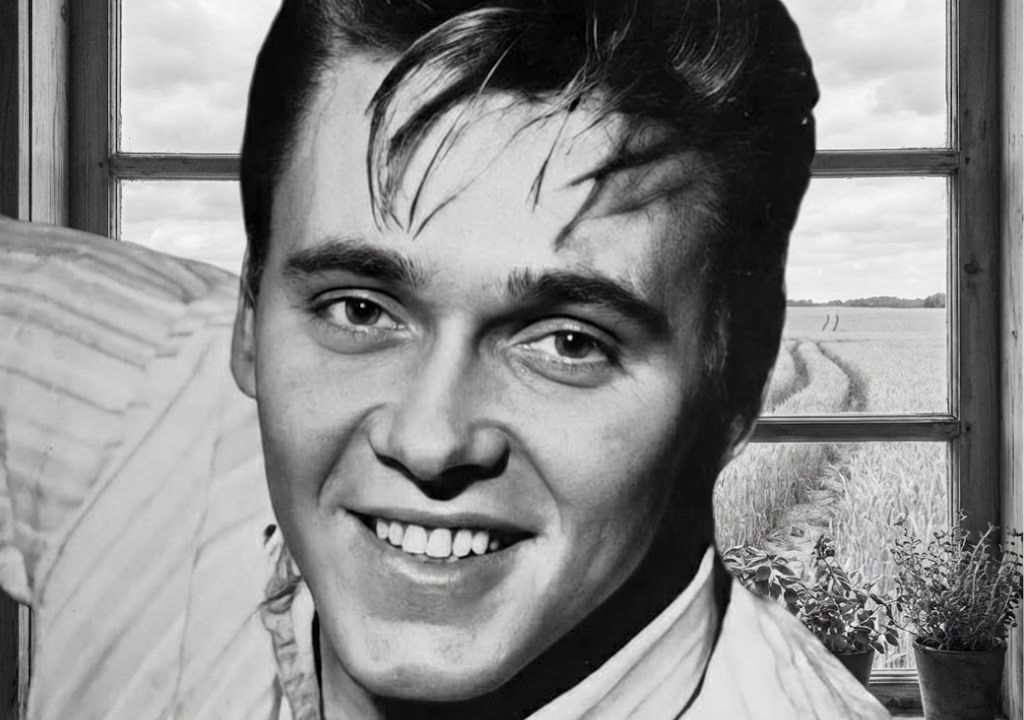

The juxtaposition between Billy Fury’s public magnetism and his private reclusiveness offers a compelling paradigm for the study of the mid-century celebrity. On stage, Fury was a visceral force, a performer whose provocative, hip-swiveling movements and “wounded” baritone drew direct comparisons to the raw sexuality of Elvis Presley. Yet, the meticulous construction of this persona was a psychological necessity rather than a cynical marketing ploy. For Wycherley, the stage served as a specialized sanctuary—a rare environment where his social inhibitions were momentarily suspended by the rhythmic demands of the music. His signature hunched-shoulder stance, which fans interpreted as a stylistic “rebel” pose, was in reality a physical manifestation of his internal tension, a literal shrinking away from the intensity of the spotlight.

This inherent vulnerability was further exacerbated by a lifelong battle with rheumatic fever, a condition that left him with a compromised heart and a persistent sense of his own mortality. This biological fragility infused his work with a pervasive melancholy that separated him from the “chipper” pop standards of his contemporaries. While his manager, Larry Parnes, attempted to pivot him toward the safety of the traditional balladeer, Fury’s most significant artistic achievement remained his 1960 debut, The Sound of Fury. As a collection consisting entirely of his own compositions, the album was an unprecedented act of self-exposure for a teenage idol. It revealed a man who found greater comfort in the meticulous observation of the natural world—Fury was a devoted birdwatcher and naturalist— than in the chaotic adulation of “Fury-mania.”

The nuance of his legacy lies in this very refusal to fully inhabit the “rock god” archetype. His interactions with interviewers were often marked by a quiet, stuttering modesty, and even at the height of his fame, he remained a loner who preferred the isolation of his farm in Wales to the social circuits of London. This perceived “innocence” became his greatest commercial asset, creating a unique bond with an audience that saw their own insecurities reflected in his eyes. He was the first British star to successfully market vulnerability as a form of strength, a strategy that would eventually influence the narrative arcs of future icons from David Bowie to Morrissey.

Ultimately, the story of Billy Fury is a testament to the power of the creative impulse to override the limitations of human nature. He did not overcome his shyness so much as he negotiated with it, using the artifice of celebrity to communicate the deep-seated emotions he could never express in conversation. When the house lights dimmed, the “Fury” would inevitably recede, leaving behind Ronald Wycherley—a man who proved that the most resonant voices are often those that whisper in the dark.