INTRODUCTION

In the austere winter of 1946, the medical infrastructure of post-war Liverpool was ill-equipped to combat the sudden onset of rheumatic fever in six-year-old Ronald Wycherley. The illness, a common but devastating streptococcal complication, launched a systemic assault on the boy’s heart, specifically targeting the delicate architecture of the mitral valve. This clinical event did not merely result in a diagnosis; it established a permanent biological metronome that would dictate the cadence of his future professional life. While his contemporaries were defined by their boundless kinetic energy, Fury began his journey with a meticulously calibrated understanding of his own physical limitations, transforming a significant medical deficit into an aesthetic virtue.

THE DETAILED STORY

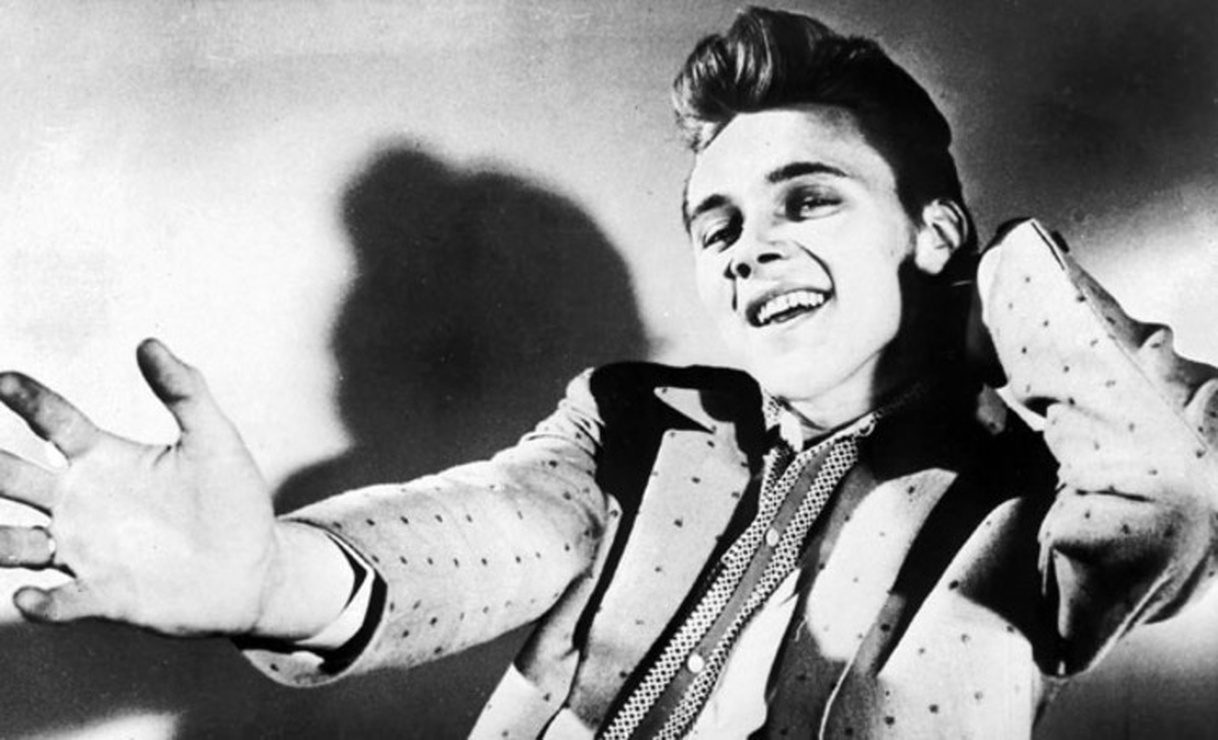

The specific pathology of Fury’s condition involved the scarring and narrowing of the heart valves, a condition known as stenosis, which forced his heart to work with an inefficient intensity to circulate oxygenated blood. By the time he transitioned into the persona of Billy Fury in the late 1950s, this physiological constraint had birthed a performance style that was revolutionary in its restraint. Unlike the frantic, high-impact choreography of his peers, Fury moved with a languid, almost feline grace—a stylistic choice that was, in reality, a necessary conservation of aerobic energy. This nuance created an aura of sophisticated mystery; to the audience at the London Palladium, he appeared to be a brooding James Dean figure, when in fact, he was a man expertly managing a persistent cardiac murmur.

This interplay between biology and brand was a precarious paradigm. During the recording of “Halfway to Paradise” in 1961, the intensity of the vocal delivery had to be balanced against the physical tax of the studio environment. His management team at Larry Parnes’ stable remained hyper-vigilant, ensuring that the grueling schedules of the “silver star” tours included mandatory intervals of rest that were framed to the public as “artistic seclusion.” Financially, this strategy was incredibly lucrative, as the rarity of his public appearances only served to increase his market value, with his 24 hit singles generating millions in revenue for the British music industry during a period of intense economic transition.

However, the psychological gravity of living with a compromised heart valve fostered a profound intellectual depth in Fury’s songwriting. He was acutely aware that his time was a finite currency. This awareness infused his work with a sincerity that resonated with a generation seeking authenticity amidst the artifice of early pop. He navigated the 1960s not as a victim of his condition, but as its master, using the unique timbre of a heart-strained voice to capture the collective imagination of millions. Even as he faced multiple open-heart procedures later in life, his legacy remained untarnished by the frailty of his pulse. Fury proved that the most enduring legacies are often built not on raw power, but on the meticulous management of a beautiful, inherent flaw.