INTRODUCTION

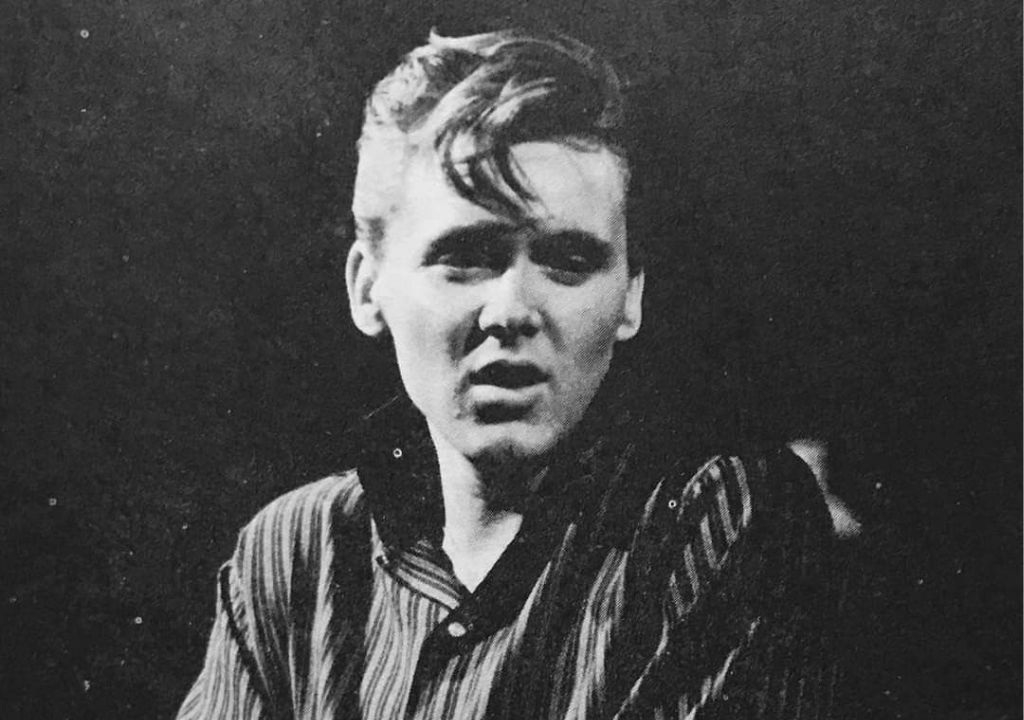

The flickering 35mm frames of Play It Cool (1962) offer far more than mere period entertainment; they represent a forensic reconstruction of a London that has long since vanished under the weight of glass and steel. In these sequences, the grain of the film captures the precise sheen of a leather jacket and the specific, smoky architecture of a Soho coffee bar with an anthropological accuracy that no modern digital reconstruction could hope to replicate. As the British Film Institute (BFI) continues its high-fidelity restorations in 2026, the cinema of Billy Fury has transitioned from a collection of “teen idylls” into a high-stakes historical archive, preserving the aesthetic DNA of a society on the precipice of a total cultural revolution.

THE DETAILED STORY

The historical importance of Fury’s filmography resides in its refusal to sanitize the environment. Unlike the glossy, detached musicals emerging from the contemporary Hollywood studio system, Fury’s early cinematic forays—specifically those directed by a young Michael Winner—utilized real locations that pulse with the raw friction of early 1960s urban life. In Play It Cool, the camera functions as a silent observer in the subterranean clubs of London, documenting the specific fashion hierarchies and social maneuvers of a generation attempting to outrun the post-war austerity of their parents. These films serve as a “gravity well” of period-correct detail, where the background noise of a passing Routemaster bus or the specific design of a mechanical cigarette dispenser provides a meticulous map of a social paradigm in flux.

When the narrative shifted to the vibrant, Technicolor palette of I’ve Gotta Horse (1965), the documentation moved from urban grit to the quintessential English seaside experience of Great Yarmouth. Shot on location at the Royal Aquarium Theatre and Britannia Pier, the film captures the high-summer energy of a British holiday culture that was about to be irreversibly altered by the advent of cheap international jet travel. Fury’s insistence on using his own animals and personal possessions—including his real-life racehorse, Anselmo—adds a layer of factual integrity that elevates the production. It is a document of a man attempting to synthesize his massive commercial power with his private, almost pastoral, sensibilities, all while the 1960s clothes and “mod” influences began to bleed into the frame.

As these works undergo exhaustive 4K restoration on 02/15/2026, the discussion has evolved beyond Fury’s performance to the broader implications of the visual archive. These films provide the only surviving visual evidence of specific Liverpool and Norfolk districts before the radical architectural “modernization” of the 1970s. They are artifacts of a time when rock ‘n’ roll was still a tactile, dangerous threat, and Billy Fury was its most visually compelling ambassador. Ultimately, the preservation of this cinematic legacy is an act of cultural stewardship, ensuring that the ephemeral spirit of the 1960s remains an authoritative, living memory rather than a fading myth. The footage does not just show us a star; it shows us exactly how the world looked when it was first beginning to scream.