Introduction

Every young musician dreams of the same thing: writing the next “Bohemian Rhapsody.” They want to create sprawling, complex, emotional masterpieces that change the world. They view commercial work—writing jingles for car dealerships or fast food—as the lowest form of artistic prostitution. They turn their noses up at the “sellouts” on Madison Avenue.

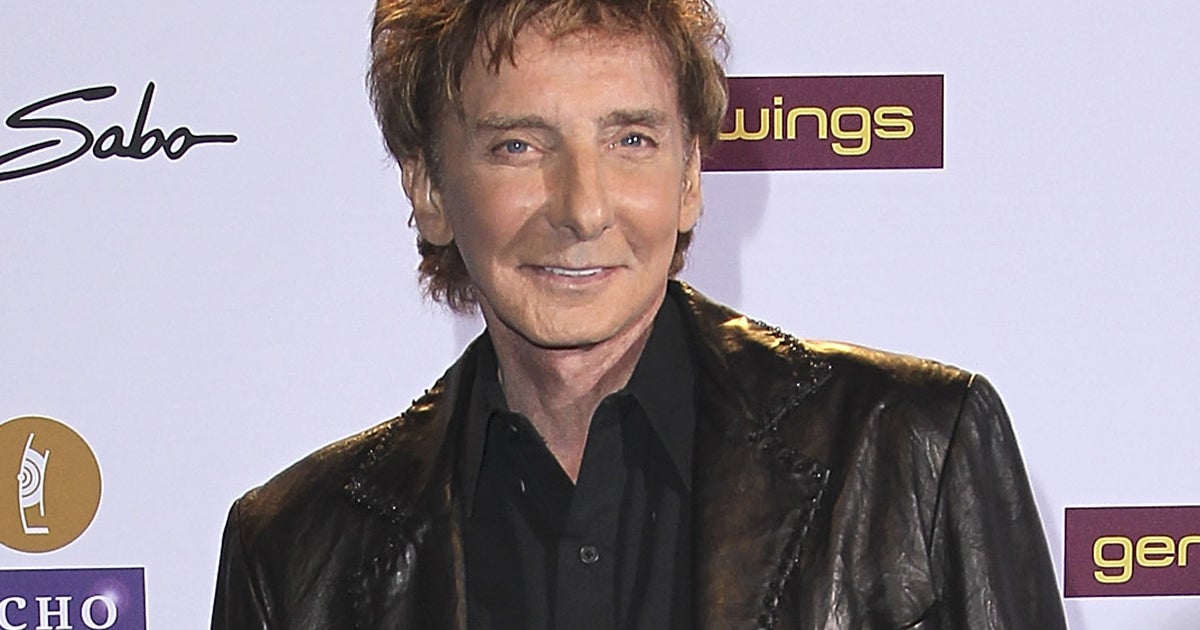

Barry Manilow thinks those young musicians are idiots.

In a move that horrified the artistic elite, the King of the Crooners declared that the “University of Jingles” was a far superior education to any music conservatory on Earth. His logic is brutal, practical, and undeniable. When you write a pop song, you have the luxury of time. You have a three-minute runway to build emotion, a guitar solo to fill space, and a bridge to find your point. You can be lazy. You can be self-indulgent.

But a jingle? A jingle is a knife fight in a phone booth.

You have fifteen seconds—maybe thirty if you’re lucky—to grab a bored, distracted housewife by the ears, plant a melody in her brain that she cannot surgically remove, and convince her to buy a specific brand of toilet paper. There is no room for error. There is no room for “artistic interpretation.” There is only the Hook.

Manilow argues that this ruthless constraint forces you to become a melodic sniper. You learn to trim the fat. You learn that if the melody isn’t instantly infectious, it’s trash. It was this “boot camp of capitalism” that taught him how to write hits like “Copacabana” and “Mandy.” He didn’t write them to be deep; he wrote them to be sticky. He applied the science of selling burgers to the art of selling heartbreak, and he realized they are exactly the same thing. While other artists were waiting for the muse to whisper to them, Barry was using the cold, hard discipline of advertising to engineer the perfect pop song.