INTRODUCTION

For a touring artist in the 1970s, the road could be a lonely place, but for Barry Manilow, it was a constant reunion. No matter which city he arrived in—be it London, New York, or Tokyo—he was greeted by familiar faces. The “Fanilows” didn’t just attend concerts; they followed the music, creating a traveling community that provided a sense of home for Barry while he was thousands of miles away from his own.

THE DETAILED STORY

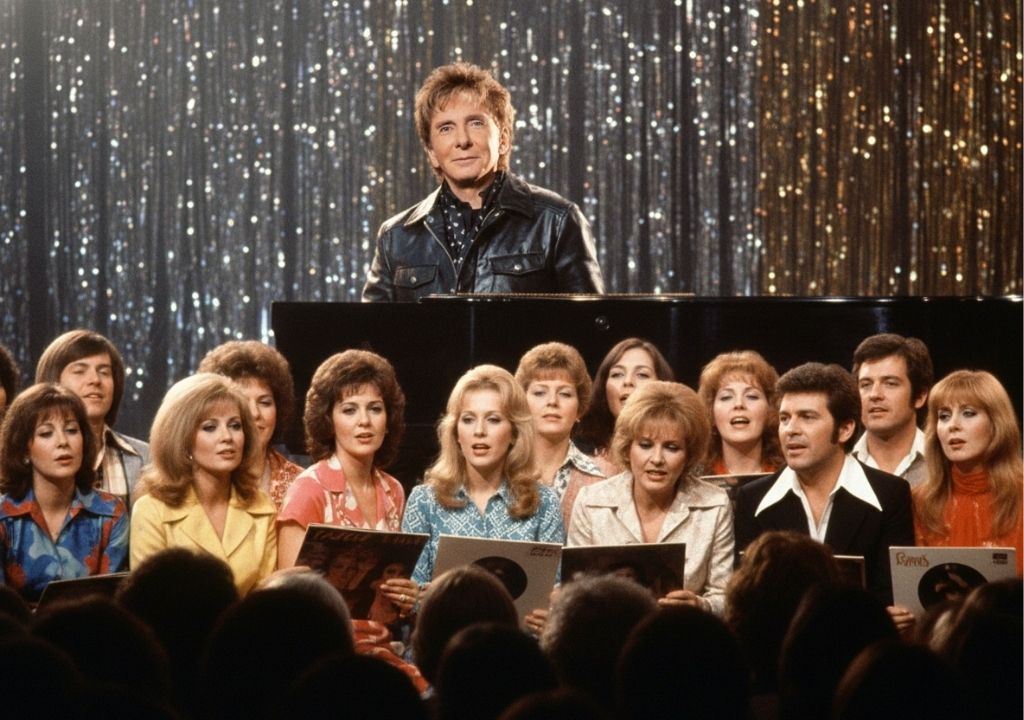

The “Front Row” culture of a Barry Manilow concert in the 1970s was something truly unique in the music industry. There was an unspoken etiquette among the Fanilows. Many of the most dedicated fans would coordinate their travel schedules to ensure that Barry always saw a friendly, familiar face in the first few rows. This wasn’t about stalking; it was about support. They knew his setlist by heart, they knew when to cheer, and they knew when to sit in rapt, respectful silence during his most tender piano solos.

Barry often spoke about the comfort this provided him. In the high-pressure world of international touring, looking down and seeing a fan who had been at the last five shows helped ease his nerves. He began to recognize them by name, often nodding to them during a song or sharing an inside joke from the stage. This level of intimacy transformed a cavernous arena into what felt like a private living room. It was a masterclass in how to maintain a “Silver Economy” connection—treating the audience not as consumers, but as friends.

The “Memory Lane” for many fans involves the “stage door” experience. After the show, regardless of the weather, hundreds of fans would wait for a glimpse of Barry. He was known for his patience, often stopping to sign autographs and exchange quick words despite the exhaustion of a two-all-out performance. These brief interactions became the foundation of legends within the fan community. One fan’s story of a five-second conversation would be shared and celebrated by the whole group, reinforcing the collective bond.

These fans also looked out for one another. If someone couldn’t afford a ticket to a second night, others would often chip in. If a fan was traveling alone, the “Mayflower” network ensured they had someone to sit with. This camaraderie turned the 1970s Manilow tours into a social movement. When we look back at those vintage photos of fans with their feathered hair and “I Heart Barry” t-shirts, we aren’t just seeing music fans; we are seeing the pioneers of modern community-building, united by a man who wrote the songs that made the whole world sing.