Introduction

The Bitter Legacy of a Legend: Inside the Decade-Long War Over Conway Twitty’s Estate

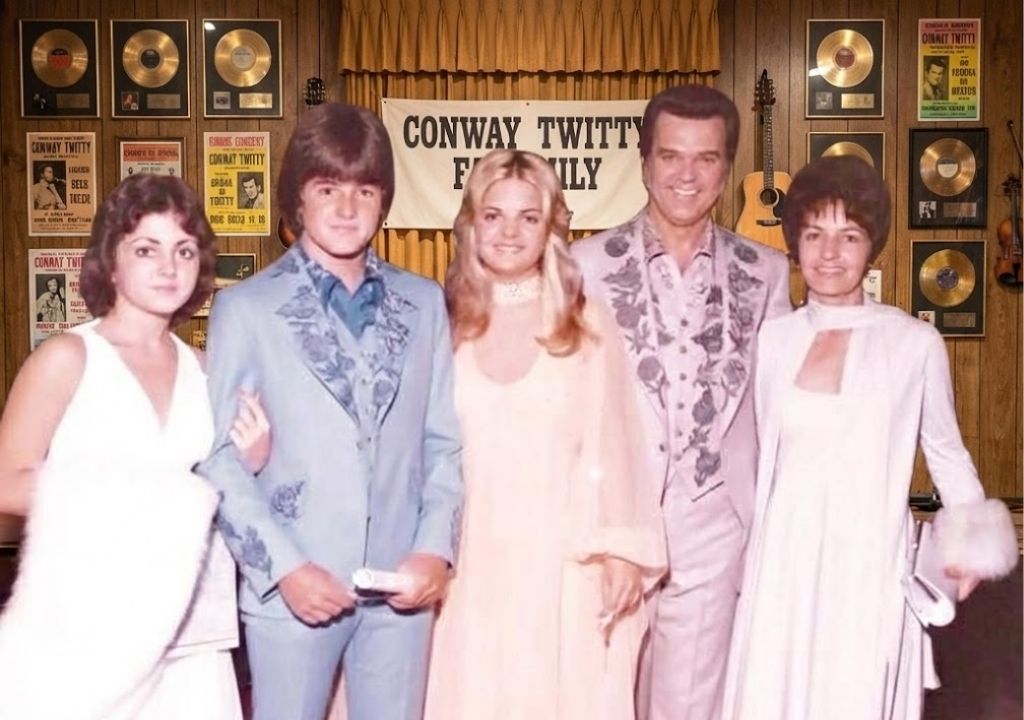

Conway Twitty was a whirlwind of productivity—a man whose ambition and work ethic turned him into a country music titan. However, while he was meticulous in his career, a single oversight in his personal planning triggered a legal firestorm that lasted over a decade. The story of Twitty’s estate is a cautionary tale about how “life happens” and how outdated documents can tear even the most loyal families apart.

The Will vs. The Law

When Conway Twitty passed away in 1993, he left behind a will that seemed straightforward: his entire estate was to be divided equally among his four children. The problem? The will pre-dated his third marriage to Dee, a woman much younger than him and close in age to his own daughters.

Under the law, Twitty’s failure to update his will didn’t mean Dee received nothing. Most states, including Tennessee at the time, provide a “Spousal Election” or “Elective Share.” This legal safeguard ensures that a surviving spouse cannot be completely disinherited, regardless of what the will says. In this case, Dee was entitled to claim one-third of the probate estate. This revelation stunned the children, who were convinced their father intended for them to be the sole beneficiaries.

The “Conway Twitty Amendment”

The tension between Twitty’s biological children and his widow became so intense that it actually changed the law. Led by his daughter Kathy, the family lobbied the Tennessee legislature, arguing that it was unfair for a spouse of a short-term marriage (six years in this case) to receive the same share as a spouse of thirty years.

Their efforts were successful. Tennessee eventually adopted what is known as the “Conway Twitty Amendment.” This law now scales the spousal elective share based on the length of the marriage—starting at 10% for short marriages and working up to the full amount over time. While it came too late to change their own case, it remains a landmark piece of legislation in probate law.

A House Divided: Executors and Auctions

The conflict extended to Twitty’s choice of executors—two longtime business managers. The children accused them of bias and vindictiveness, but the court refused to remove them, honoring Twitty’s original selection.

Perhaps the most tragic chapter was the auction of Twitty’s personal property. Because the heirs and the widow could not agree on how to divide tangible items—memorabilia, musical instruments, and scrapbooks—the judge ordered a public sale. Because the children’s livelihoods were tied to Twitty’s enterprises and they lacked immediate liquidity, they often found themselves unable to outbid others for their father’s most cherished possessions.

The Lesson of the “Third Act”

The litigation surrounding the $15 million estate (roughly $45–50 million in today’s value) serves as a stark reminder: estate planning is not a “set it and forget it” task. Whether due to the head injury Twitty suffered in 1990 or a simple human tendency to procrastinate, his failure to account for his “blended family” resulted in a legacy defined as much by courtrooms as by hit records.