Introduction

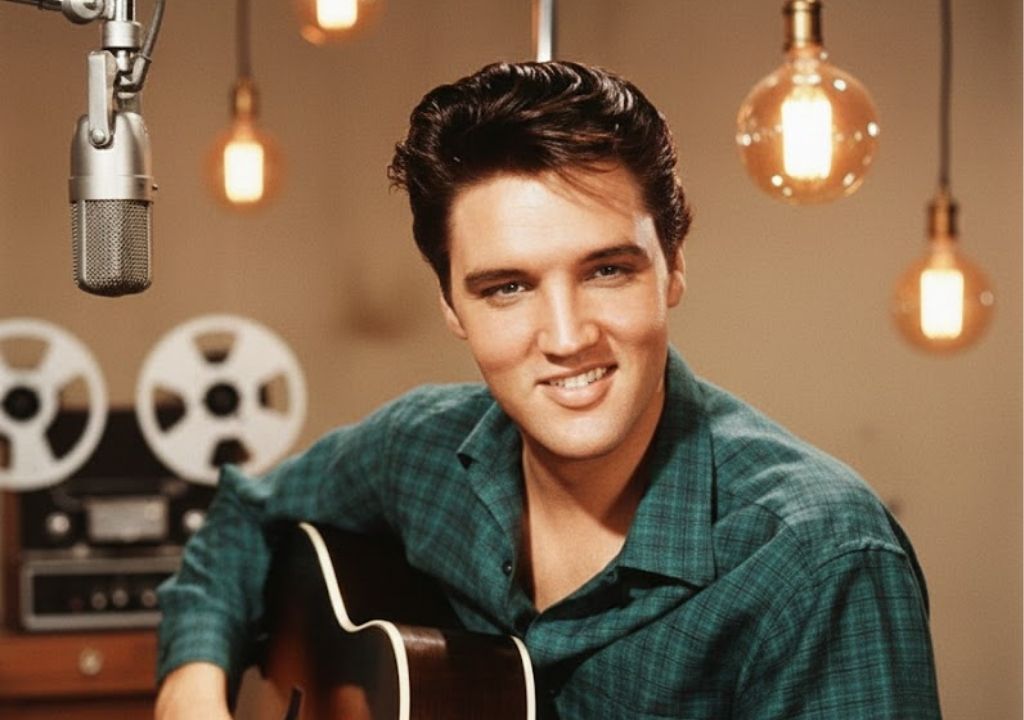

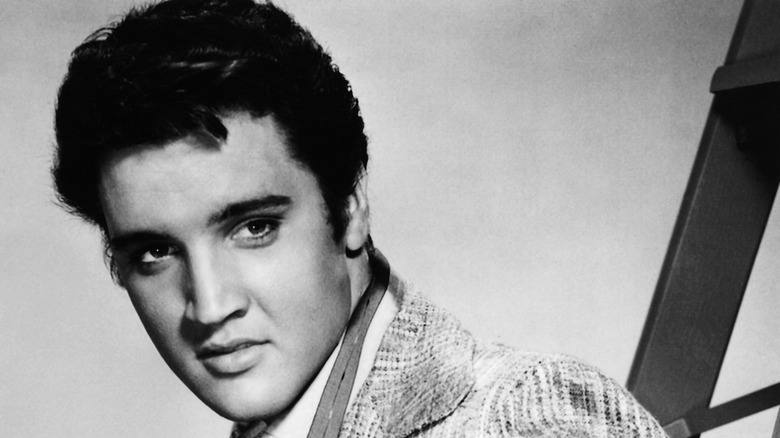

In a shocking moment that stunned fans and reporters alike, James Brown made a rare confession about Elvis Presley, revealing a truth few dared to voice. When asked about Elvis’s influence, Brown leaned back and calmly declared, “People talk about Elvis being the king, but I was the one who taught the king how to move.” His words, at first met with nervous laughter, sparked controversy and ignited debates about music, race, and legacy.

But Brown’s statement wasn’t born out of jealousy. It reflected years of experience, struggle, and observation. Coming from the segregated South, Brown knew the hardships black performers faced. While he and others were banned from television, a white artist from Tupelo—Elvis—was showcasing moves rooted in the same rhythm and spirit that defined soul. Brown recognized the talent, the fire, and the pain in Elvis’s performances, even if the public saw only rivalry.

Brown’s confession highlighted a complex bond between the two men. Behind the headlines, there was mutual respect. Brown acknowledged that Elvis had not stolen the soul of black music but had been influenced by it, carrying it into new spaces for audiences who otherwise would never have experienced it. In private, James Brown had long admitted that Elvis treated him with respect, but the world demanded conflict and competition.

Their connection became clearer in a backstage encounter during the mid-1960s. Brown recalled Elvis entering the room with calm confidence, saying, “You don’t know me, but I know you.” For over an hour, they spoke of gospel, juke joints, and the pressures of fame, recognizing shared struggles behind their different paths. Both were “prisoners of performance,” bound by the demands of an audience and society, yet driven to turn their hardship into music.

Brown later reflected that Elvis had opened doors, taking black music into white households, while enduring hatred and scrutiny. Brown himself had fought similar battles from the other side of the color line. Both men were shaped by poverty, gospel, and the need to be seen and understood. By the end of his life, Brown stopped framing Elvis as a rival and began referring to him as a brother, acknowledging the shared spirit and pain that fueled their artistry.

:no_upscale()/imgs/2022/09/12/09/5580998/0f61fa952d35096cf9ae6f22e2f580f6c6298d6e.jpg)

Ultimately, Brown’s confession wasn’t about rivalry—it was about truth. “Elvis didn’t steal the soul. He felt it,” he said. Brown recognized that music transcends race; it belongs to the soul. Both legends had turned struggle into art, bridging worlds and shaping American music. By the time of his death in 2006, James Brown had left behind not just funk, but a perspective that honored the intertwined legacies of two men who carried America’s contradictions and transformed them into timeless rhythm.