INTRODUCTION

The relentless heat of central Texas in 1939 didn’t just bake the earth; it tempered the spirits of those who survived it. At six years old, Willie Nelson stood in a cotton field in Abbott, his small hands calloused by labor that would break a grown man in the modern era. While the American economy lay in ruins, Nelson was receiving a different kind of currency—a mail-order Stella guitar that cost his grandparents exactly $6.00. In this desperate landscape, where the stakes were nothing less than daily survival, the foundations of a $25,000,000 musical empire were being laid in the black-land soil.

THE DETAILED STORY

The narrative of Willie Nelson is often distilled into the “Outlaw” archetype, yet his origin story is a meticulous study in the discipline of the Great Depression. Abandoned by his parents shortly after birth, Nelson was raised by his paternal grandparents, Alfred and Myrtle Nelson. They were not merely caregivers but architectural influences on his psyche. As music teachers by trade, they instilled in him the “Smith Method,” a rigorous pedagogical approach to rhythm and melody that provided a structured counterpoint to the chaos of the 1930s. This early exposure created a sophisticated paradox: a boy who was socially marginalized but musically sophisticated.

Abbott, Texas, was a town of only 300 people, yet it served as a global crossroads for the young Nelson. In the local church, he absorbed the soaring, communal hope of Protestant hymns; in the cotton fields alongside migrant workers, he discovered the raw, rhythmic truth of the blues. This synthesis was inevitable. By age ten, Nelson was already a professional musician, earning $8.00 a night playing in polka bands and Bohemian clubs—a staggering sum for a child during an era where adult laborers earned far less. These performances were not mere recreation; they were essential economic contributions to a household defined by scarcity.

This early proximity to hardship cultivated the zen-like detachment that would later define his “Red Headed Stranger” persona. Nelson learned that while external circumstances—like a collapsing economy or a failed harvest—were beyond one’s control, the internal architecture of a song was a territory where one could achieve absolute sovereignty. His meticulous, behind-the-beat phrasing is a direct descendant of those Abbott afternoons, a refusal to be rushed by the ticking clock of a world that demanded too much too soon.

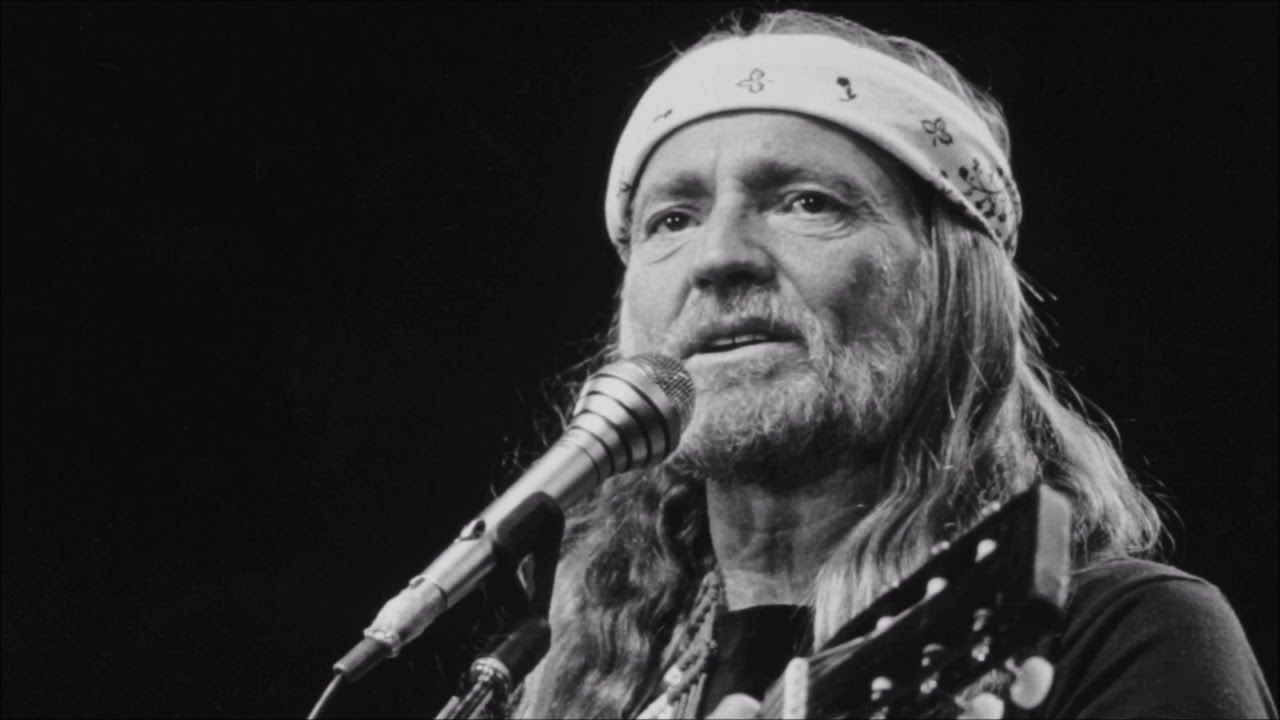

As we evaluate Nelson’s legacy in 2026, we see a career that has spanned nearly a century of American history. The “Red Headed Stranger” is not a rebel by choice, but a survivor by design. His story remains an authoritative reminder that the most enduring American icons are often forged in the coldest fires of deprivation. The dust of the Great Depression didn’t bury Willie Nelson; it provided the grit necessary to build a legacy that remains unshakeable.