INTRODUCTION

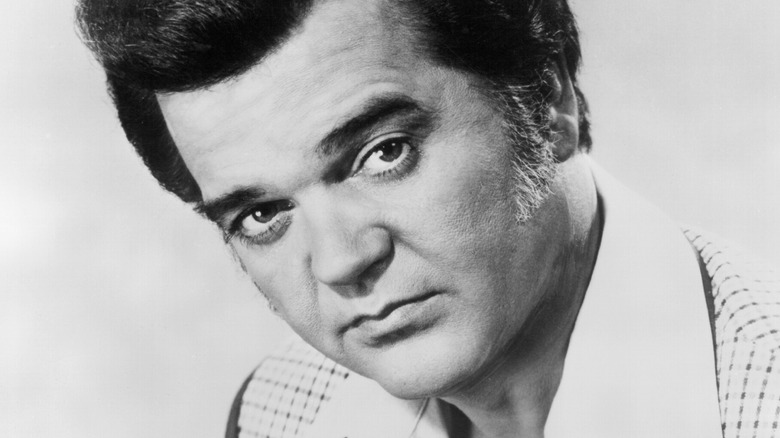

The static on the AM radio dial in late 1958 carried a voice so eerily familiar that thousands of listeners across the United States immediately telephoned their local stations to request “the new Elvis Presley record.” Yet, the artist on the revolving 45 RPM disc was not the King of Rock and Roll, but a former minor-league baseball prospect from Mississippi who had recently adopted the moniker Conway Twitty. This moment of vocal convergence triggered one of the most sophisticated debates in the early rock-and-roll paradigm: where does profound influence end and structural imitation begin? For Twitty, the success of “It’s Only Make Believe” was simultaneously a commercial triumph and a technical indictment that would take years of meticulous artistry to resolve.

THE DETAILED STORY

The core of the historical critique regarding “It’s Only Make Believe” was never centered on a stolen melody—the song was a meticulously crafted original composition by Twitty and Jack Nance—but rather an appropriation of the Presley “aesthetic.” At the time, the Billboard charts were dominated by the specific, rhythmic phrasing and baritone-to-tenor leaps that Presley had popularized. Twitty’s performance, particularly the dramatic, octave-jumping crescendo in the final verse, mirrored Presley’s architectural approach to the power ballad with startling precision. Industry insiders and rival executives at the time argued that Twitty was a manufactured doppelgänger, an inevitable byproduct of a market desperate to fill the vacuum left by Presley’s enlistment in the U.S. Army.

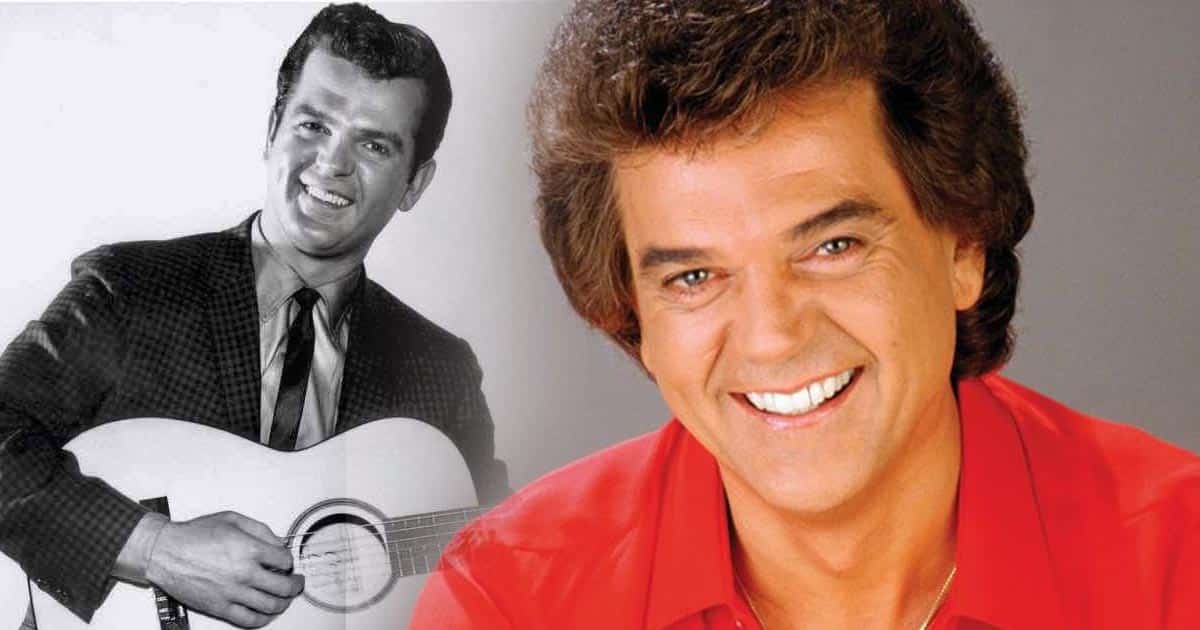

However, a closer musicological analysis reveals a distinct divergence in their vocal philosophies. While Presley’s style was rooted in a blend of gospel and rhythm-and-blues, Twitty’s delivery possessed a darker, more deliberate sense of longing that would eventually become the foundation of his country music dominance. The “Elvis clone” label, while statistically significant for initial sales—the record eventually sold over eight million copies—failed to account for Twitty’s own structural innovations. He was not merely mimicking; he was refining a specific type of romantic vulnerability. By the time he transitioned to Nashville in the mid-1960s, the comparisons had evaporated, replaced by an authoritative recognition of his unique “Twitty Growl.”

Ultimately, the paradox of “It’s Only Make Believe” is that it utilized a familiar paradigm to launch a career of singular independence. The harsh comparisons of 1958 served as a high-stakes crucible, forcing Harold Jenkins to develop a meticulous sense of self-awareness that few of his contemporaries achieved. It confirms that in the high-stakes architecture of the music industry, the most inevitable way to transcend an icon is to first master the language they created, then rewrite it entirely. As of 2026, the song stands not as a copy, but as a definitive cornerstone of the American romantic canon.