INTRODUCTION

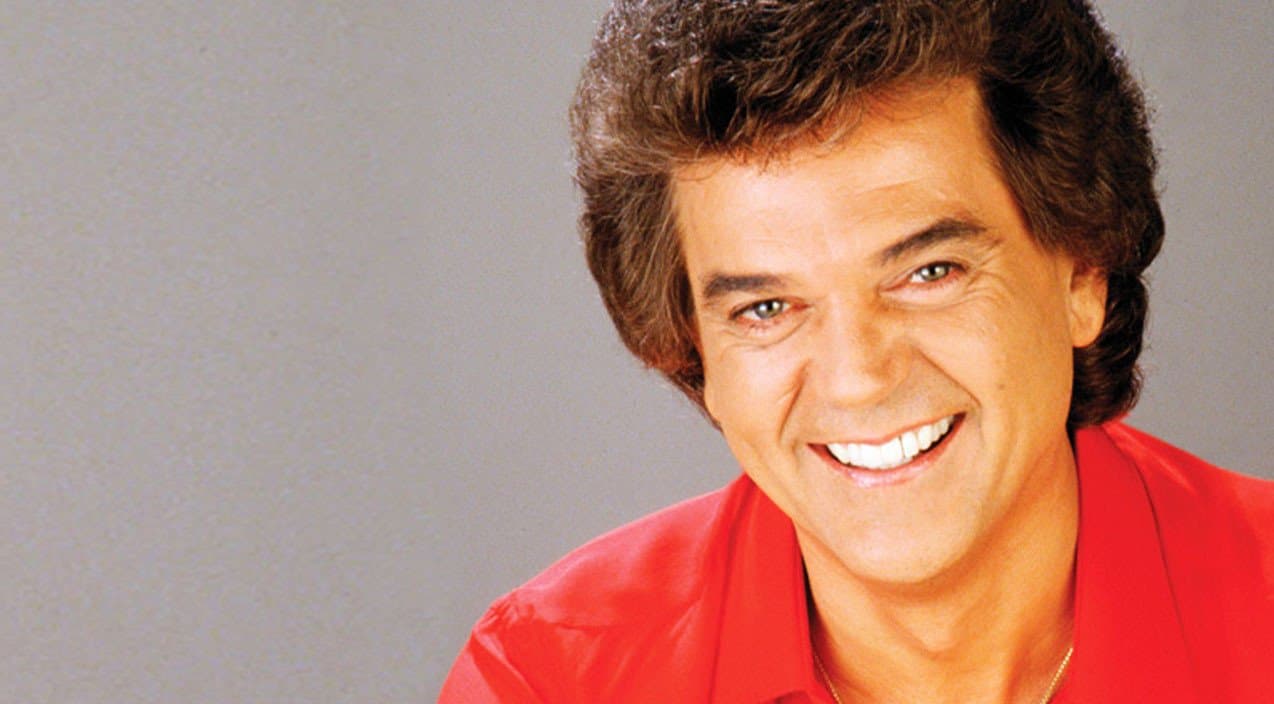

The neon hum of a Nashville honky-tonk is the traditional sanctuary for the weary country singer, a place where the adrenaline of a three-hour set is slowly dissolved in a glass of amber whiskey. Yet, for Harold Lloyd Jenkins—the man the world knew as Conway Twitty—the ritual of the “after-party” was a foreign language he refused to speak. On any given night during his three-decade reign, while his band, the Twitty Birds, navigated the rhythmic chaos of local bars, the “High Priest of Country Music” could be found in the blue light of a hotel television, meticulously absorbing the late-evening news. This was not a symptom of antisocial behavior, but a calculated pillar of a narrative architecture built on total professional discipline. For Twitty, the transition from the rock-and-roll stage to the country pantheon in 1965 was more than a genre shift; it was a moral and physical pivot toward a lifestyle of asceticism that allowed him to maintain a staggering 55 number-one hits until his untimely death in 1993.

THE DETAILED STORY

The paradox of Conway Twitty lay in the friction between his persona and his practice. On stage, he was a master of the “steamy” ballad, a man whose low, tremulous baritone on tracks like “Hello Darlin'” or “You’ve Never Been This Far Before” could command an almost religious devotion from his audience. Yet, once the final modulation of “It’s Only Make Believe” faded, the “High Priest” vanished. His discipline was industrial. He famously imposed a “no drinking” rule for his band members while on the clock, viewing his performances not as a party, but as a meticulous contract between himself and the fans who had paid their hard-earned USD ($) to see him. This work ethic was forged in his early years as a professional baseball prospect for the Philadelphia Phillies and refined during his service in the Korean War. To Twitty, a tour was a military-grade operation where the primary objective was the preservation of the voice and the image.

By choosing the newsroom over the barroom, Twitty maintained a level of mental clarity and longevity that eluded many of his contemporaries. His hotel room routine was his “quiet center,” a place where he could shed the high-collared suits and the meticulously coiffed hair—what critics called the “Roman centurion” look—to become the unpretentious Harold Jenkins once more. This separation between the man and the myth was essential; it prevented the self-destruction that was so prevalent in the country music industry of the 1970s and 80s. He was a “straight-laced” outlier in an era of outlaws.

This dedication to his fans extended beyond the hotel walls. He was known to stay for hours after a performance, signing every last autograph, often outlasting the venue’s janitorial staff. Only when the last fan was satisfied would he retreat to his bus or room to catch up on global events. This commitment to the “Ordinary and Necessary” (as the U.S. Tax Court would later describe his business expenses in a landmark 1983 ruling) ensured that his legacy was built on reliability. When he collapsed on his tour bus in Branson, Missouri, on June 5, 1993, he died as he had lived: on the road, in a state of professional readiness, having given everything to the stage and nothing to the nightlife.