INTRODUCTION

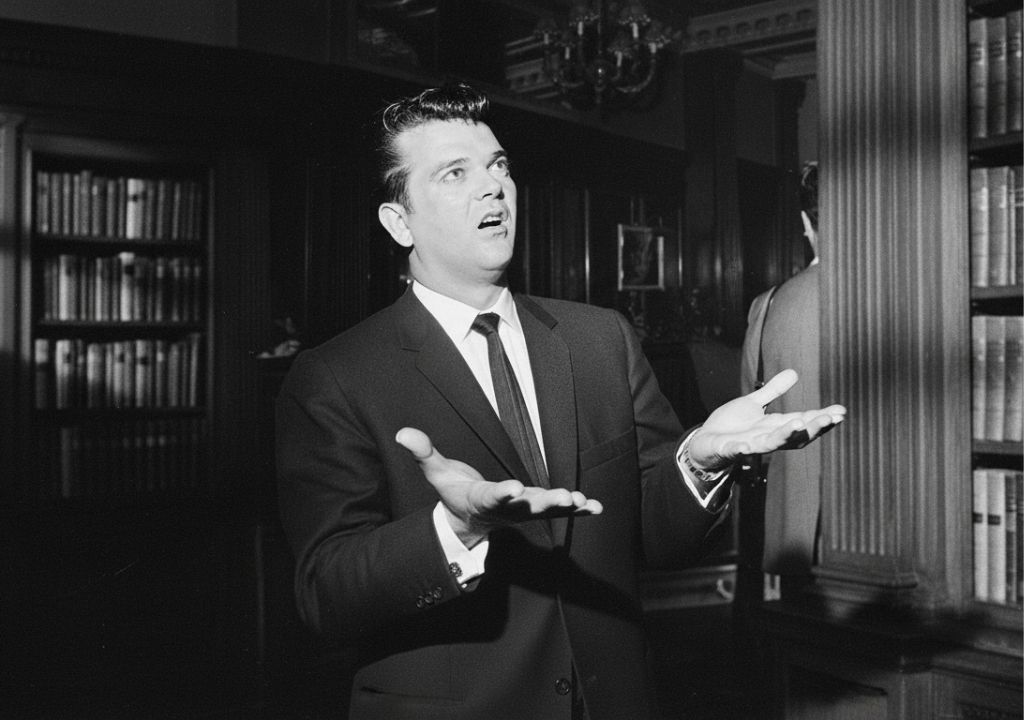

At 03:00 AM on 08/12/1975, somewhere on the desolate stretch of I-40 between Nashville and Tulsa, the interior of the “Twitty Bird” custom coach was a masterclass in controlled intensity. Under the low glow of recessed lighting, Harold Jenkins—the man the world revered as Conway Twitty—sat at a small table, his focus so absolute it bordered on the architectural. For Twitty, these nocturnal poker sessions were not a pursuit of leisure; they were a rigorous mental exercise in probability and human psychology. As the stack of USD grew before him, representing the combined per diems of his entire band, the atmosphere grew thick with a unique brand of professional tension. He was a man who had been scouted by the Philadelphia Phillies for his precision on the mound, and that same unyielding discipline was now being applied to the five-card draw.

THE DETAILED STORY

The narrative of Conway Twitty’s poker prowess offers a profound insight into the leadership paradigm of one of country music’s most enduring titans. Twitty was meticulous in all things, from the “growl” in his vocal delivery to the strategic management of his multi-million dollar enterprise. On the tour bus, the poker table served as a microcosm of his broader philosophy regarding excellence and meritocracy. He did not play for the sake of the gamble; he played to win, viewing the game as a test of the same mental fortitude required to maintain fifty-five consecutive number-one hits. His bandmates, seasoned musicians in their own right, frequently found themselves outmatched by Twitty’s uncanny ability to read a “tell” or calculate odds with the speed of a mainframe computer.

By the time the sun began to crest over the horizon, it was not uncommon for Twitty to have “cleaned out” his companions, leaving them with empty pockets and a renewed respect for their employer’s intellectual lethality. However, it was at this precise moment of total fiscal conquest that the true complexity of Twitty’s character emerged. With the same quiet authority he used to command a stage, he would meticulously count the winnings and return every cent to his players. This was not an act of pity, but a sophisticated exercise in psychological stewardship. He demanded that they play at their highest level, pushing them to the brink of loss to sharpen their instincts, yet he refused to profit from their inevitable defeat.

This ritual established a fascinating interpersonal dynamic: a high-stakes environment where the ultimate goal was not the accumulation of wealth, but the perfection of the pursuit itself. Twitty understood that his legacy was built on the collective strength of his team, and these games were his way of fostering a culture of sharp wits and resilience. He occupied the role of both the predator and the protector, a nuance that reflected the dual nature of his public persona as the “Master of the Slow Hand.” It suggests that for a man of Twitty’s stature, the greatest victory was not found in the prize, but in the undisputed proof of mastery. Can a leader truly be considered a peer when their dominance is so absolute that even their generosity feels like a lesson?