Introduction

The lens of the Mitchell BNC camera in the early 1960s did not merely record a singer; it captured the tectonic shifts of a nation in transition. In 1962’s Play It Cool, directed by Michael Winner, we witness a Britain caught in a profound liminal state. The bomb sites of the Blitz were finally being paved over by the slick, chrome-heavy aesthetic of the jazz-pop era, yet the shadows of post-war austerity lingered in every alleyway. Ronald Wycherley, the Liverpool deckhand known to the world as Billy Fury, moved through these scenes with a singular, quiet intensity. He was the vessel through which the burgeoning “teenager” identity was first truly articulated in British cinema—not as a loud caricature of American rebellion, but as a uniquely British blend of stoicism, vulnerability, and latent energy.

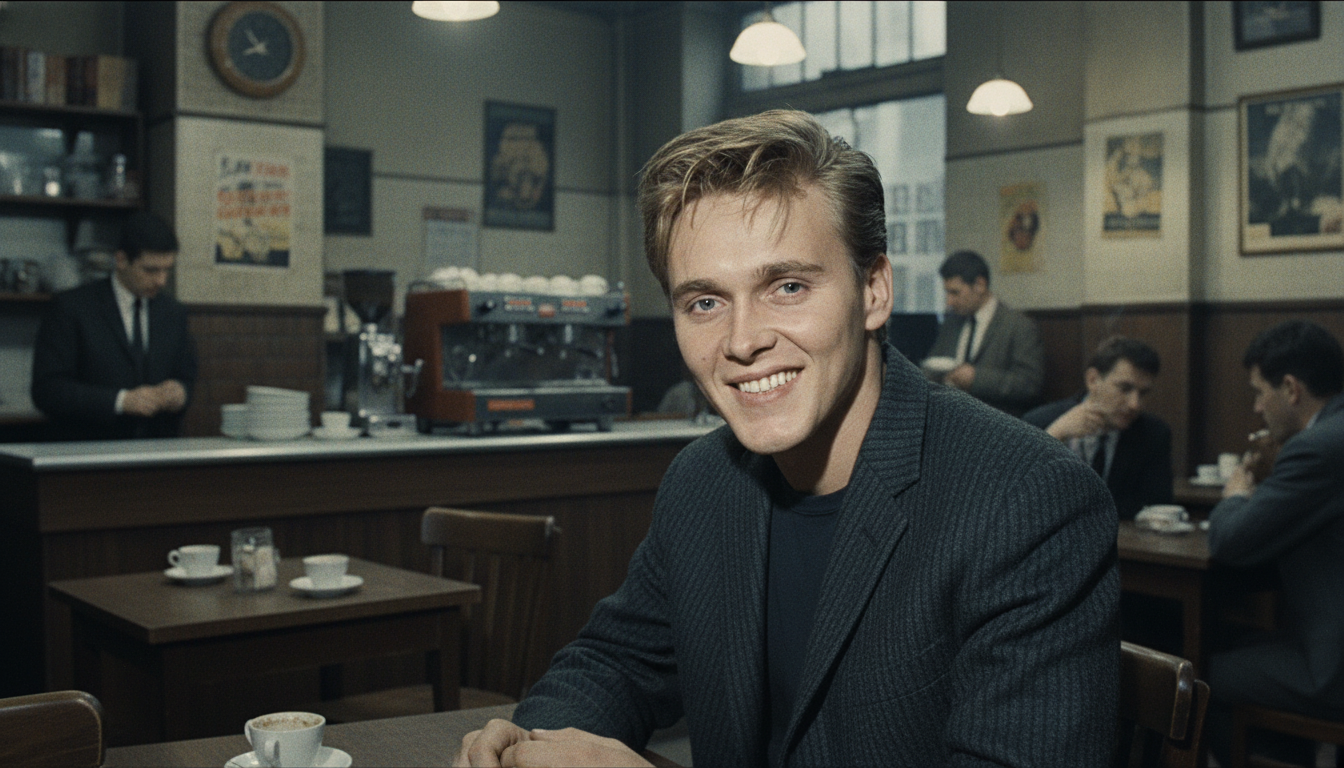

This cinematic output, once dismissed by contemporary critics as ephemeral “teen fodder,” has undergone a quiet transmutation into essential sociopolitical documentation. Every frame of Fury’s filmography acts as a meticulous repository for the granular details of 1960s life. We see the specific, heavy texture of a mohair suit, the chaotic geometry of a Soho coffee bar, and the lingering social hierarchies of an England that was just beginning to find its voice. Unlike the hyper-stylized Technicolor fantasies emerging from Hollywood at the time, Fury’s films often leaned into a gritty realism that mirrored the “Kitchen Sink” drama movement. In his 1965 feature, I’ve Gotta Horse, the narrative dissolves into a semi-autobiographical study of his own obsession with animals, providing a rare, unvarnished look at the sanctuary he built at his farm—a stark contrast to the hysterical, neon-lit crowds of the New Victoria Theatre.

The “Golden Thread” connecting these works is the tension between the curated idol and the authentic, fragile man behind the persona. While the scripts often demanded a two-dimensional heartthrob, Fury’s naturalistic performance style—characterized by long, contemplative silences and a subtle, shifting gaze—revealed a deeper nuance. He was an inadvertent archivist of the “Liverpool Sound” and the “Merseybeat” atmosphere before it was polished into a global commodity. To watch these films in 2025 is to witness the birth of a paradigm; we see the influence of the “Big Three” and the shadow of the Casbah Coffee Club before the British Invasion changed the world forever. The films preserve the specific, transient energy of a London that was about to become “Swinging,” yet still carried the scent of coal smoke and old leather.

Furthermore, the “Information Density” within these films provides a sociographical map of a lost world. The background characters, the vintage transit systems, and the very quality of light in a pre-digital London are locked within the celluloid. Fury was, in essence, the ghost in the machine of British Pop. His refusal to embrace the frantic, aggressive pace of the industry allowed him to leave behind a more intimate, localized record of his own culture.

The resolution of his cinematic legacy is now clear: Billy Fury was never just a singer who dabbled in film. He was a silent witness to a cultural revolution. His films remain as vivid and fragile as the man himself—a permanent ledger of a Britain that exists now only in the flickering light of a projector, inviting us to reflect on the nature of fame and the inevitable passage of time.