INTRODUCTION

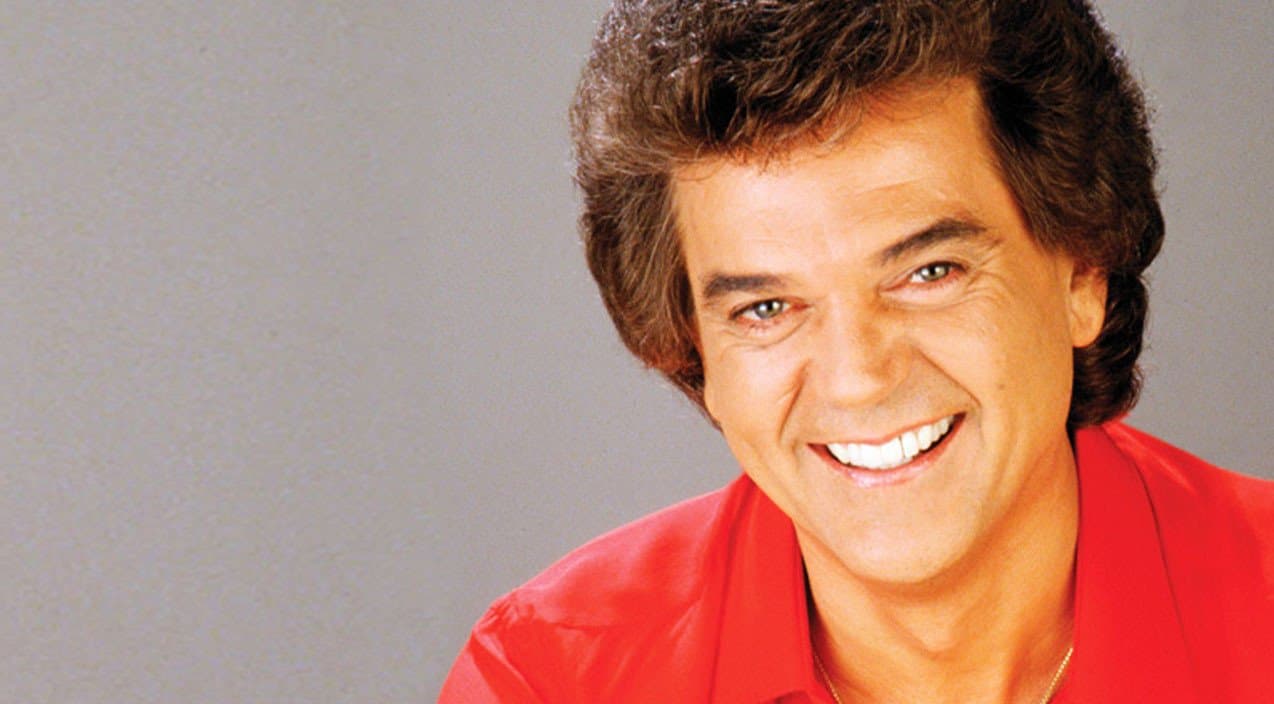

The scouting report on a young Harold Lloyd Jenkins was as rhythmic and precise as the ballads he would eventually master. With a staggering .450 batting average in high school, the future Conway Twitty was not merely a local standout; he was a surgical technician with a Louisville Slugger. By the early 1950s, the Philadelphia Phillies had seen enough of the Arkansas native to offer a professional contract, setting the stage for a career in the dirt and sun of the Major Leagues. Yet, on the very day the ink was meant to meet the page, a different draft intervened. The U.S. Army claimed Jenkins for service in the Far East, fundamentally altering the trajectory of American entertainment. While he would eventually become the “High Priest of Country Music,” the ghost of a professional ballplayer remained his constant companion, haunting the periphery of every sold-out arena.

THE DETAILED STORY

The narrative architecture of Twitty’s life is defined by a meticulous discipline that is more characteristic of a professional athlete than a rockabilly rebel. Stationed in Japan between 1954 and 1956, Jenkins managed to keep both of his internal flames alive, playing on the local Army baseball team while forming his first band, the Cimarrons. When he was finally discharged, the Philadelphia Phillies renewed their offer, but the world had shifted. During his service, Jenkins had witnessed the meteoric rise of Elvis Presley and the raw, kinetic power of Sun Records. The choice became a paradigm of personal sacrifice: the certainty of the diamond versus the volatility of the stage. He famously recalled, “I threw down the baseball bat and picked up the guitar,” a decision that resulted in a record-breaking 55 number-one hits, yet left a lingering sense of “what if” that he carried until his death on June 06, 1993.

This underlying passion for baseball was not a discarded hobby but a foundational element of his adult identity. Unlike his peers who sought refuge in the excesses of the road, Twitty’s “shopping” and investment habits were strictly architectural and athletic. In 1982, he channeled his significant earnings—accrued from an empire valued in the millions of USD ($)—into the Nashville Sounds, a minor league team that allowed him to finally inhabit the front office of the sport that had once been his destiny. He even built a professional-grade ball field for the local Little League in Hendersonville, Tennessee, ensuring that the opportunities he nearly missed were available to the next generation. This commitment suggests a profound truth: Twitty viewed music as his meticulous profession, but baseball was his unrequited soul.

On the David Letterman Show in 1989, Twitty spoke with an authoritative calm about his alternate life, admitting that in his heart, he was still the boy with the .450 average. This raises a significant implication for his legacy: was the “High Priest” persona a role he played with surgical precision because he understood the technicality of performance, rather than the lifestyle of the artist? The quiet, ascetic nature of his tour life—watching the news in hotel rooms while his band hit the bars—mirrors the disciplined focus of an athlete in training. As we reflect on his storied career in 2026, we find an artist who didn’t just write the songs; he engineered a legacy of success to fill the void left by a dream deferred.