INTRODUCTION

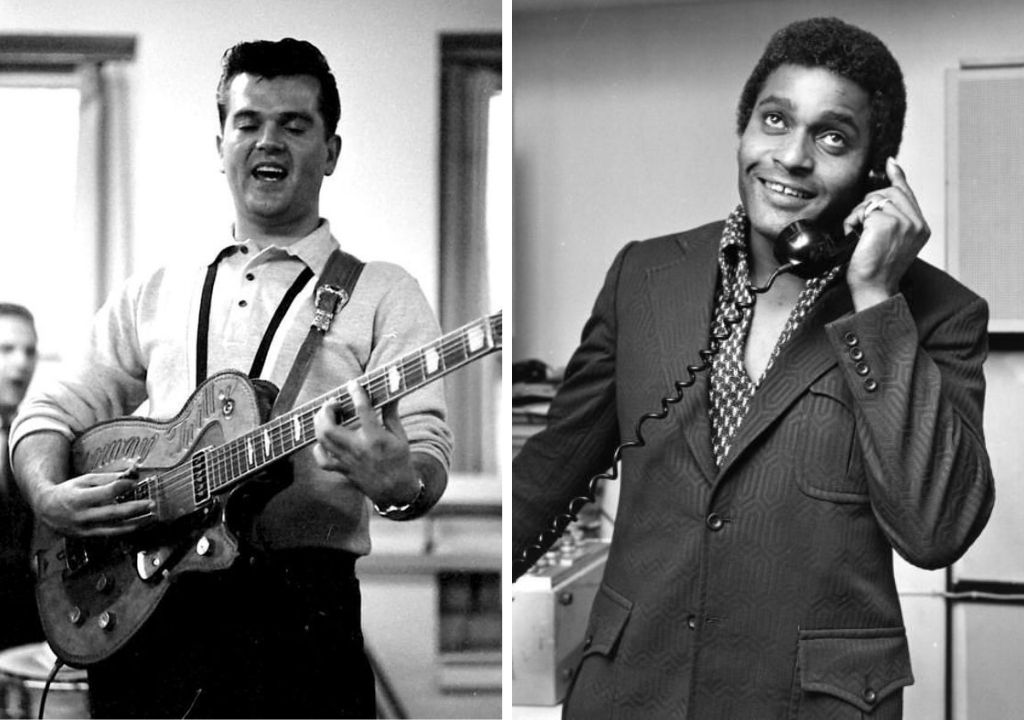

On the sweltering evening of 08/14/1967, the backstage corridor of a grand auditorium in the Deep South felt like a pressure cooker of cultural tension. Charley Pride, the first Black superstar of country music, stood preparing to face a crowd whose expectations were often clouded by the rigid racial paradigms of the time. Nearby, Conway Twitty, already an established titan of the genre, did not offer a rehearsed speech or a grand political gesture. Instead, he simply walked toward the stage alongside Pride, his presence acting as a silent but impenetrable shield against the friction of the era. This was not merely a professional courtesy; it was a meticulous declaration of a friendship that would challenge the very foundations of the Nashville establishment.

THE DETAILED STORY

The country music scene of the 1960s was a fortress of traditionalism, frequently resistant to any shift in its demographic composition. When Charley Pride emerged, his success was an anomaly that many industry executives were unsure how to navigate. Conway Twitty, however, recognized an artistic peer rather than a cultural disruptor. Their bond was forged in the shared language of vocal precision and the arduous, often isolating demands of the touring circuit. Twitty’s advocacy for Pride was never performative; it was woven into the fabric of his professional conduct. By sharing stages and public spaces with Pride at a time when such associations carried significant risk to one’s USD-generating capacity, Twitty utilized his substantial social capital to normalize Pride’s presence in the genre.

This partnership was rooted in a profound mutual respect for the craft. Twitty, the “Master of the Slow Hand,” and Pride, the man who would become a member of the Country Music Hall of Fame, understood that the emotional truth of a song was fundamentally colorblind. There were instances where Twitty’s firm stance ensured that Pride received the same accommodations and respect as any white headliner, effectively rewriting the narrative of who “belonged” in the hallowed halls of country music. The relationship was not without its nuances, as both men had to navigate the expectations of their respective fanbases while maintaining a meticulous standard of personal integrity.

Twitty’s commitment to Pride reflected a broader humanistic paradigm. He saw the inevitable evolution of the genre and chose to be an architect of progress rather than a relic of the status quo. Their friendship thrived because it was built on the mundane—shared meals, late-night conversations about the mechanics of a melody, and the quiet camaraderie of the road. This normalcy was their most potent weapon against prejudice, proving that the boundaries of culture are often more fragile than the bonds of individual character. The legacy of their connection serves as a definitive testament to the power of quiet influence, raising an authoritative thought: is the most enduring form of social change found not in the roar of the crowd, but in the steadfast loyalty of a single, meaningful friendship?