INTRODUCTION

On a quiet afternoon in May 1971, the neon signs of the last Twitty Burger location flickered out, marking the definitive collapse of a venture that had once promised to rival the giants of the American fast-food industry. For many entrepreneurs, this would have been the moment to seek the cold sanctuary of bankruptcy law, shielding personal assets from the fallout of a corporate failure. However, the man known to the world as Conway Twitty operated under a different paradigm. To Twitty, the $1 million in capital raised from friends, fellow artists like Merle Haggard, and business associates wasn’t just a financial liability; it was a debt of honor. The decision he made in the wake of this collapse would eventually lead him from the grease-stained kitchens of Oklahoma to the hallowed chambers of the U.S. Tax Court, creating a legal precedent that remains studied by scholars today.

THE DETAILED STORY

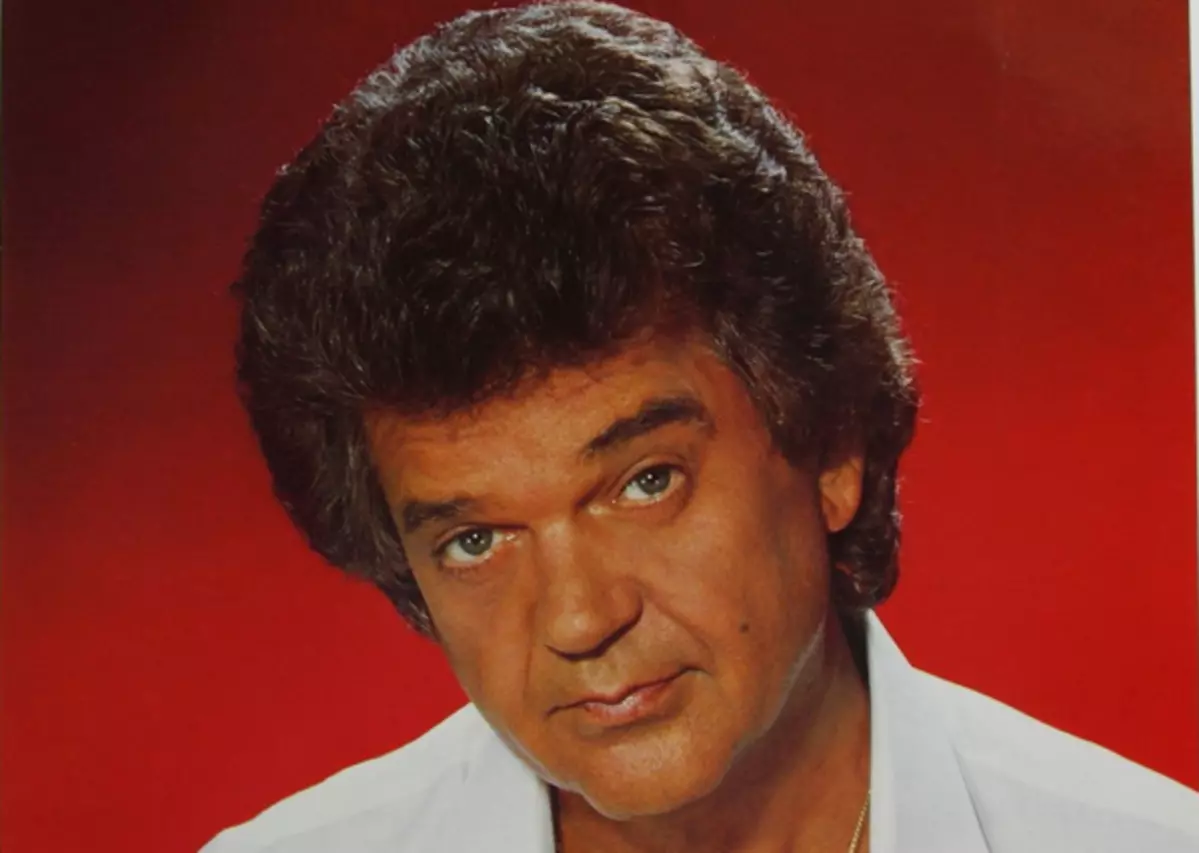

The failure of Twitty Burger, Inc. was not due to a lack of ambition but perhaps an excess of it. Launched in 1969, the chain featured a signature burger topped with a pineapple ring—a culinary nuance that failed to capture the national palate. When the venture disintegrated, Twitty found himself at a crossroads. While he had no legal obligation to reimburse the 75 investors who had backed his vision, he understood that in the ecosystem of country music, reputation is the only currency that never devalues. He feared that the “cloud” of a failed business might alienate his fan base and professional peers, tarnishing the meticulously crafted image of the “High Priest of Country Music.”

Driven by this strategic integrity, Twitty began a multi-year mission to repay every cent of the lost investments using his personal earnings from a grueling touring schedule. By 1973 and 1974, he had funneled nearly $100,000 back to his associates—a sum he subsequently deducted from his federal income taxes as an “ordinary and necessary” business expense. The Internal Revenue Service, however, viewed these payments as a non-deductible moral gesture rather than a professional necessity, sparking the landmark case Jenkins v. Commissioner.

The ensuing 1983 trial became a masterclass in narrative architecture. Twitty’s counsel argued that for a performer of his stature, personal integrity was inextricably linked to commercial viability. The court eventually ruled in Twitty’s favor, recognizing that protecting one’s business reputation is a legitimate professional expense. The presiding judge, Irwin L. Deutsch, was so moved by the testimony that he famously penned a poetic “Ode to Conway Twitty” in the official court footnotes, concluding that “it was the moral thing to do.” This victory did more than settle a tax bill; it cemented Twitty’s legacy as a man whose word was as sovereign as his voice. He proved that while burgers may fail, the value of a name, when defended with meticulous honor, is an asset that transcends the volatility of any market.