INTRODUCTION

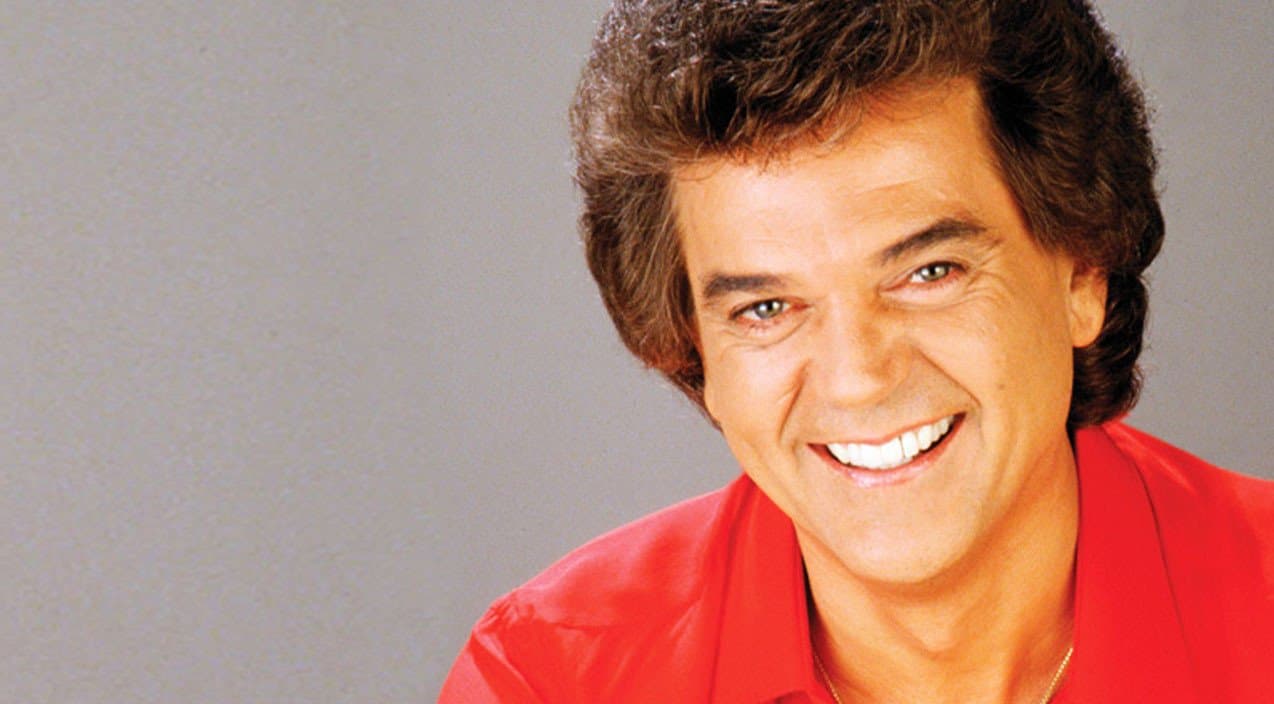

The aluminum skin of the Hawker Siddeley HS.125, gleaming with the distinctive “Twitty Bird” livery, represented the apex of country music’s mid-century economic expansion. By the late 1970s, Conway Twitty had ascended to a level of stardom where the traditional tour bus—a rolling sanctuary for most Nashville icons—seemed insufficient for the rigorous demands of his 300-show-a-year itinerary. Yet, as the cabin door sealed shut and the pressurization hiss filled the cabin, the man who project-managed the emotional lives of millions was often descending into a state of profound, medicinal detachment. This was the central irony of Twitty’s jet-set era: he owned a multi-million dollar vessel for the clouds, yet his biological architecture was fundamentally designed for the terrestrial security of the Mississippi delta.

THE DETAILED STORY

The phenomenon of aviatophobia among high-performance individuals is a fascinating study in the nuance of control. For Conway Twitty, a man whose professional life was a meticulous exercise in precision—from the exact frequency of his vocal growl to the pristine condition of his “meat and three” meals—the transition from the earth to the sky represented an inevitable surrender of agency. While his private jet, the Twitty Bird 1, provided the strategic speed necessary to maintain his record-breaking chart dominance, it simultaneously placed him in a paradigm of vulnerability. To navigate this psychological friction, Twitty relied on a disciplined regimen of sedation, often requesting that his staff assist him into a deep, chemically assisted slumber before the aircraft even taxied toward the runway.

This aversion to flight was not a sign of fragility, but rather an expression of his deep-seated commitment to the “grounded” persona that his audience found so relatable. On the ground, Twitty was the master of his domain, navigating the American highways in a custom bus that functioned as a mobile command center. In the air, however, he was a passenger to physics. His peers in the industry often remarked on the paradox of a man who would invest in the most advanced aerospace technology of the era only to spend the duration of the flight in a state of suspended consciousness. It was a calculated trade-off: he sacrificed his comfort for the efficiency required to reach the fans who saw him as their romantic surrogate.

As we look back through the lens of 2026, Twitty’s struggle with flight serves as an authoritative reminder that the “High Priest of Country Music” was subject to the same human anxieties as his listeners. His reliance on sedation was a meticulous management of a personal fear, ensuring that the “myth” of the unstoppable showman remained intact for the audience waiting at the destination. Eventually, the psychological toll led him to sell the aircraft and return to the rhythmic, predictable safety of the tour bus—the “Twitty Bird” on wheels. This choice confirmed that for Harold Jenkins, the ultimate luxury was not the speed of the jet, but the intellectual peace of knowing the ground was always within reach.