Introduction

The history of mid-century pop culture is littered with “what ifs,” but few are as poignant as the phantom American career of Ronald Wycherley. To the British public, he was Billy Fury, a performer of such raw, instinctive magnetism that he was frequently hailed as the only legitimate European answer to Elvis Presley. Yet, while his contemporaries crossed the Atlantic to seek the neon validation of Hollywood, Fury remained tethered to the gray, pastoral shores of England. The question of why he never “cracked” America is not a story of lack of talent, but a complex intersection of physiological fragility and a profound, quiet defiance of the stardom machine.

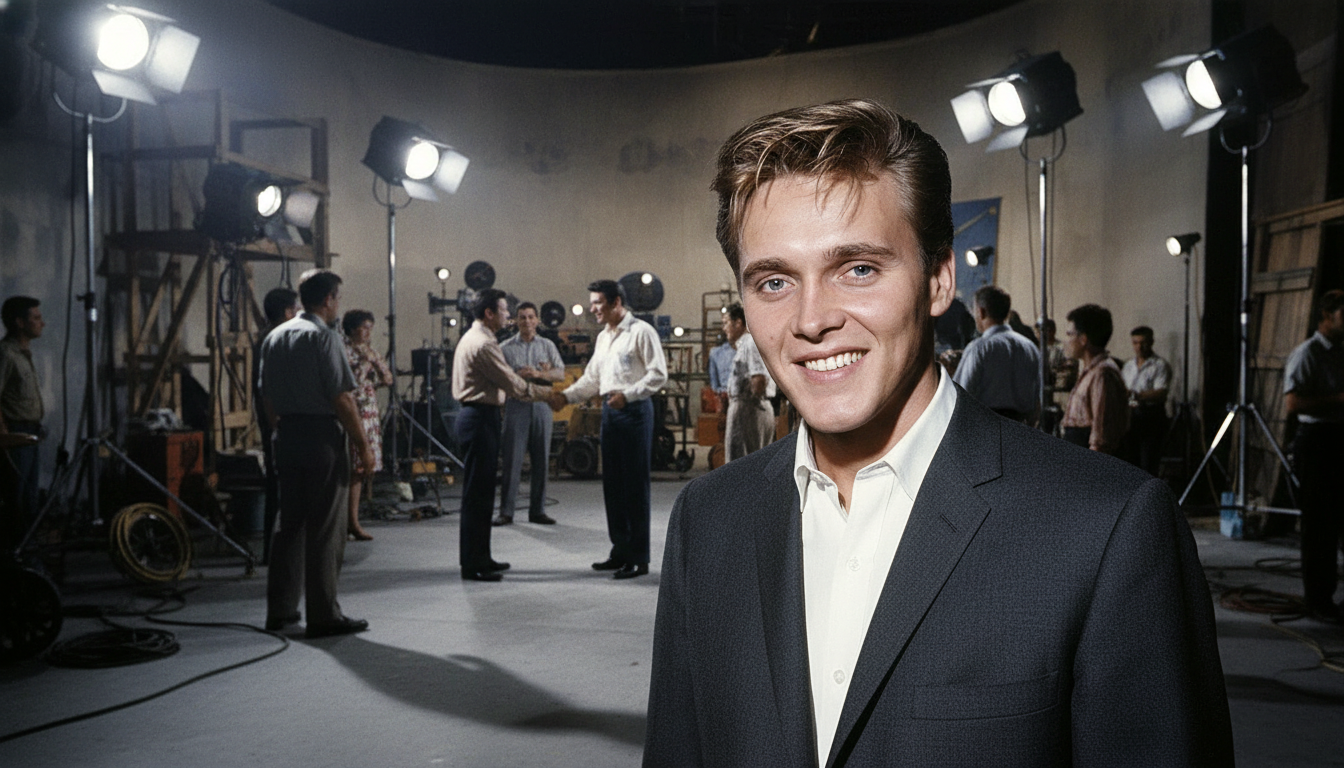

The most concrete opportunity for a Hollywood transition occurred in 1962. Amidst a whirlwind of publicity, Fury and his manager, Larry Parnes, flew to Los Angeles. The centerpiece of the trip was a meticulously staged meeting with Presley on the set of Girls, Girls, Girls. To the cameras, it was a summit of rock-and-roll royalty. Behind the scenes, however, it was an exercise in contrast. Fury was a man of “meticulous reserve,” overwhelmed by the industrial scale of the American studio system. While the infrastructure for a screen test was arguably within reach, the momentum stalled.

The “Golden Thread” of this failure was Fury’s heart—a heart permanently scarred by childhood rheumatic fever. For Fury, a career in Hollywood wasn’t just a matter of logistics; it was a gamble with mortality. The grueling pace of American film production and the inevitable “whirlwind tours” required to sustain a US presence were seen by those closest to him as a potential death sentence. His manager, the notorious Larry Parnes, operated on a high-volume, low-risk paradigm. Parnes favored the guaranteed revenue of British “package tours”—exhausting bus circuits of UK cinemas—over the massive, unhedged investment required to break a solo artist in the States. By the time the British Invasion began in 1964, the paradigm had shifted; the American market was hungry for “groups,” and the era of the brooding solo idol had reached its twilight.

There was also the nuance of Fury’s own soul. Unlike the hyper-ambitious stars of the era, Fury possessed a “studied detachment” from his own fame. He was a man who famously felt more at home among his horses and the wild birds of his farm than in the artificial glare of a film studio. He viewed the mechanics of the industry with a gentle skepticism, lacking the predatory hunger for global dominance that defined the Elvis trajectory.

Resolution came not through a spectacular failure, but through a graceful withdrawal. Billy Fury did not lose Hollywood; he simply chose a different, quieter legacy. He remains the great “lost” icon of the Atlantic—a man who possessed the charisma to conquer a continent but the wisdom to know that his true “wondrous place” lay far from the hollow prestige of the Hollywood hills.