INTRODUCTION

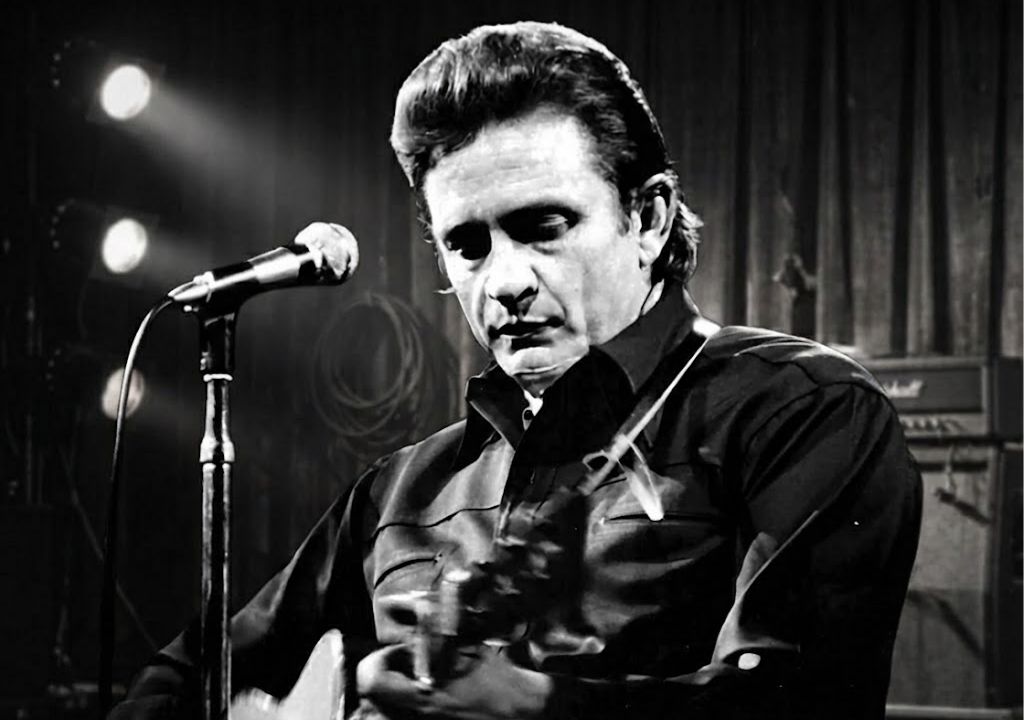

On the evening of April 17, 1970, the air inside the White House was heavy with the scent of high-stakes diplomacy and the faint, lingering tension of a divided nation. Johnny Cash, dressed in his trademark black, stood beneath the portraits of past leaders, preparing to perform for Richard Nixon. This was not a routine visit for a musical legend; it was a deliberate entry into the inner sanctum of power. While the cameras captured the surface-level cordiality of the event, the underlying atmosphere was one of profound ideological friction, as the “Man in Black” prepared to speak truth to the most powerful man on the planet regarding the systemic failures of the American penal system.

THE DETAILED STORY

The confrontation began before a single note was played. President Nixon, seeking to align his administration with the conservative “silent majority,” had specifically requested that Cash perform “Okie from Muskogee” and “Welfare Cadillac”—songs that mocked the anti-war movement and criticized those on public assistance. Cash’s refusal was not an act of arrogance, but a meticulous defense of his moral architecture. He recognized that complying would be an inevitable surrender to a political narrative that dehumanized the very people he represented. Instead, he pivoted the evening’s trajectory, choosing a setlist that functioned as a sonic indictment of the socio-political status quo Nixon sought to uphold.

As he launched into “What is Truth” and “The Ballad of Ira Hayes,” the paradigm of the evening shifted from entertainment to advocacy. Cash used the prestige of the White House to give voice to the Native American struggle and the disillusionment of a generation. However, his most sophisticated maneuver occurred beyond the spotlight. During his visits to Washington, including his 1972 testimony before the Senate Subcommittee on National Penitentiaries, Cash presented a clear, data-driven memorandum on prison reform. He advocated for vocational training and a shift away from purely punitive incarceration, arguing that true national security began with rehabilitative justice.

This meeting remains a pinnacle of celebrity advocacy. While Nixon’s response was characteristically pragmatic, the sheer audacity of Cash bringing the grievances of the “beaten down” to the President’s desk solidified his legacy. He proved that an artist’s role is not merely to entertain, but to serve as a bridge between the powerful and the powerless. Cash left the White House having neither surrendered his integrity nor his monochrome uniform, leaving behind a legacy of confrontation that continues to challenge the American political conscience. He demonstrated that true authority is found in the nuanced representation of the human condition, even in the face of the highest office.